Standardized testing is failing our students

Aaron Anderer via Flickr (Creative Commons)

Alexa Murphy argues standardized testing fails students.

November 4, 2022

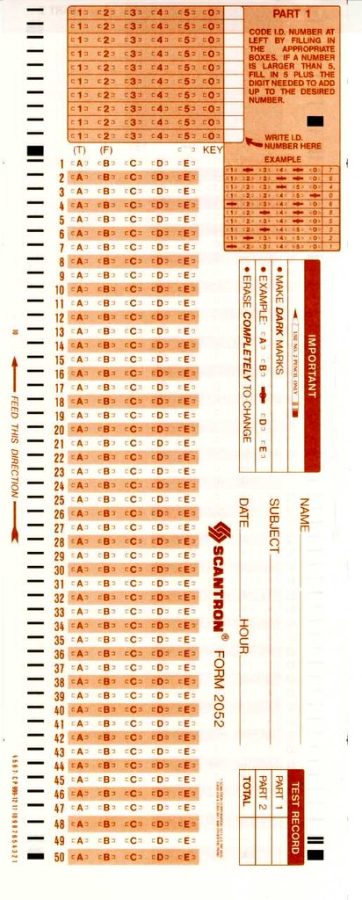

Every year, hundreds of thousands of students file into dimly lit testing rooms, where the sounds of ticking clocks and whirring fans are just loud enough to muffle quick heart beats, awaiting the ScanTron sheet that will help decide their academic futures.

For upperclassmen, just hearing the acronyms “ACT” and “SAT” often yield a visceral response. Students cringe, or groan, or shift uncomfortably. It’s the same sense of dread that becomes plainly visible when one asks a Junior where they plan on applying to university.

Standardized testing and college applications are two facets of high school that are simply too stressful to dwell on in our daily lives. More than that, they encourage a kind of short-term learning that favors a small number of very privileged students, and undermines the passion for learning that schools hope to instill in their pupils.

We as students assign excessive gravity to standardized test scores, despite its decreasing value in the college admissions process. The so-called objectiveness enforces the notion that one’s grade on the SAT is a measure of one’s overall intelligence, never mind the fact that standardized tests are only designed to measure academic value in a manner digestible for university admissions teams. On the SAT and ACT websites, the ratio of correct to incorrect answers as indicated by a series of bubble letters is said to reveal one’s readiness for college.

This understanding of what it is that college admissions-based standardized tests measure tends to foster unproductive academic environments, as students obsess over how one arbitrary grade will reflect their educational performance after highschool. For students, the format of standardized tests does not lend itself well to missions promulgated by schools across the country, missions prioritizing critical thought, skill development, and perseverance.

“Throughout life you’re taught to have smaller incentives to build up to a larger goal, but standardized testing doesn’t support that sort of method that school teaches you otherwise,” said student Eli Savage ‘24. “It’s weird and contradictory and puts a lot of pressure on students who are young teenagers.”

These young teenagers are impressionable, and to teach students to interpret their intellectual capacities in reference to a number out of 36 or 1600 means to limit their ability to grow as a learner.

The other day, I was faced with the choice to complete two hours of ACT prep or spend those two hours reading a Hannah Arendt book that had spent months collecting dust. I opted for the ACT prep, because I knew that it would serve me better in the short term. The other thing I knew was that my family can’t afford a tutor, so just in order to be on par with many of my peers in the exam room, I would have to put in the extra hours.

That brings me to my next point. When colleges can discern a child’s entire intellectual value in one number, many families quickly realize that the only way in which their child can be accurately represented in applications is through extra tutoring and counseling. This is fine logic, and it speaks, more than anything, to a medium that prioritizes ScanTron-centric critical thought over real-life intellect.

These advantages thus create an academic hierarchy within the very top level of an existing academic hierarchy. We at Masters are extremely fortunate to be here. Just by nature of attending this prestigious institution, we as students represent the peak of educational opportunity in America. In accordance with this, shouldn’t we then expect to earn the highest test scores in America, sans tutors?

In reference to this, Adam Gimple, director of college counseling, said, “There is nothing about our pedagogical approach as an institution that prepares students to sit for 3+ hours and take a standardized test. Our final exams don’t go for more than 90 minutes. So what is it about our experiences as an institution that is standardized in a way that is the equivalent experience of a standardized test?”

The test doesn’t care about the critical thought we’ve honed through years of Harkness discussions. The test doesn’t care that we’re restless for the 70 minutes we spend in history class, forget about three consecutive hours. The test wants us to train ourselves how to take it, not through reasoning and creativity, but through bubbling in the correct answer, and through sitting still for longer than any lecturer could speak in university. The exam demands very specific test taking skills only really accessible through textbooks distributed by the testing organization itself, or by professionals who have dedicated significant time and resources to understanding the mechanisms by which the test grants you a clean 36.

Students do not need another arbitrary metric by which to rank their intelligence, particularly when this metric is merely a reflection of various forms of privilege and luck. If factors such as wealth, neurotypicality, and cultural background can play a role in the number that appears on your SCOIR profile, perhaps we should consider a future in which we not only feel comfortable applying test optional—which many students already do—but in which we allow ourselves to rethink the way we conceive of intellect.