New look at “War and Peace”: why we need to recognize and study Russian imperialism

As a result of the imperialist policies of the Russian Empire, the USSR, and modern Russia, many cultures and whole ethnic groups were close to being erased. Instead of unique cultural identities of variuos colonized nations, Russia for centuries imposed the one “great” Russian identity, forcing its language and culture on other peoples.

March 14, 2023

When I come across the “aesthetics” reels on Instagram about Anna Karenina or the shabby panel buildings of the former USSR or see my American peers put communist symbols on their laptops, I wonder if they would similarly celebrate the British empire or the US colonists. When I think of the USSR and Russia, I do not see the cute images or political ideals. I think of their imperialistic policies, my family, my people and many other nations, whose history and culture was either stolen or ridiculed and who were subjected to endless poverty and persecutions by Moscow rulers.

The challenge of recognizing Russian colonial imperialism comes mainly from a West-centered view on the issue. In the more well-known examples of British or French Empires, colonization was rooted in racism, which was not always the case in Russia. Moreover, the conflict between Russia and the West caused many to associate the former with being an anti-West and, thus, anticolonial power. While the first assumption is not false, the second one is far from being true.

In the early 20th century, when colonialism finally started to lose support in the West, Moscow began to broadcast an image of an anti-colonial champion to international audiences. Lenin even famously named colonialism the final stage of capitalism. Putin in his recent speech about the illegal annexation of several Ukrainian regions called Russia’s actions “decolonization” and in 15 minutes mentioned the word “colonialism” 11 times. Despite such rhetoric, the Russian empire, the USSR and now Russia have continued to build typical colonial structures inside their borders.

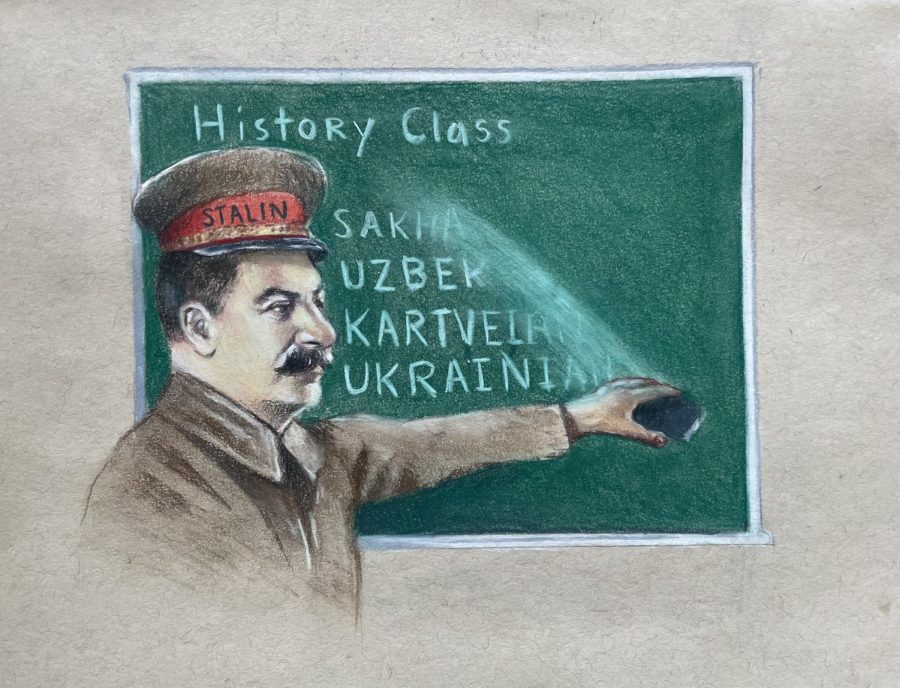

The prominent feature of imperialism is the economical and social divide between center (Russia/Moscow) and the periphery (Eastern Europe, Baltic States, Caucasus, and Central Asia). Such inequality is usually achieved through the centralized control and disregard for the needs of the colonized nations, economic and social oppression, and forcible assimilation, which leads to identity loss and cultural erasure. For example, both the USSR and Russian Empire, have long imposed “the great” Russian language and culture on many indigenous and subjugated peoples forcing them to lose their cultural identity. The execution of a whole generation of Ukrainian writers known as “The Executed Renaissance,” the massive deportation of Ukrainians to isolated parts of the USSR, the Ems Ukaz that prohibited publishing of literature in Ukrainian, and Brezhnev’s Circular that promoted the study of the Russian language are just a few examples of Russia’s colonial policies against Ukraine. Similar examples can be found for any other nation subjugated by Moscow.

Nataliia Kulieshova ‘23 recounts the stories of her grandparents about the forced russification of her hometown Slovyansk in Donetsk region of Ukraine.

“My great grandparents [with their children] were sent from Russia to [the Donetsk] region in the mid-60s to teach “uneducated” Ukrainians to work harder, and to make them “better” and more like their “Big Brothers” [Russians],” Kulieshova said. “My grandma told me that when she came to my hometown, it was all in Ukrainian. Everyone spoke Ukrainian and no one really spoke Russian. Then the russification policies took place, and everyone was forced to switch to Russian. Every billboard, every shop name [had to be] in Russian. And people were forced to study Russian in school. It was just really forced for many many years, and when I was born there, my home town was pretty much all Russian-speaking. It took a long time for the Ukrainian language to become more popular there.”

Colonial imperialism would have been impossible to sustain without the belief system it promoted. To justify the oppression of other countries, the empires such as the USSR or Russian Empire often reinforce the idea that their people are superior to other nations and, thus, have some inherent right to rule and oppress them. The propaganda of such ideas often elevates the colonizers’ culture (even if a lot of it is stolen) and ridicules the culture of the colonized people. For example, in Soviet and Russian media, the language of the oppressed countries has often been portrayed as stupid, aimed for the village or at most for the family dinners, while Russian language has been depicted as intelligent, the language of science and education. Similarly, the clothing, rituals, history, and literature of colonized people have been made fun of and simplified to cliches.

Such propaganda becomes so deeply ingrained in the minds of people who live in the empire that it is impossible to point out the media produced by the empire’s center that does not somehow support those stereotypes. Russian literature is no exception.

While recognizing the imperialist ideas in the works of many Western writers, most American and European readers prefer to ignore similarly dangerous ideas in the Russian literature. Without a very clear understanding of Russian colonialism, Western audiences often do not notice the subtle imperialist motives and descriptions present in the majority of Russian works. For example, the beloved Dostoyevsky in his “Diary of a Writer,” celebrates Russia’s victory in Turkmenistan (another Russian colony) and expresses his hope for people “all the way to India” to “become convinced of the invincibility of the white tsar.” Pushkin in his poem “The Prisoner of the Caucasus” commends the violent subjugation of the Caucasus people and proudly declares that “everything is subject to the Russian sword.” Tolstoy in his novel “War and Peace” disregards the perspective of Polish people, who supported Napoleon, and modifies the actual history of Vilnius meeting Tsar Alexander I to further elevate the Russian army. Lermontov in his novel “A Hero of Our Time” repeatedly describes the indigenous people of Caucasus as uncivilized and tries to construct a sympathetic character out of Russian officer Pechorin, who kidnaps and abuses a Circassian woman. Virtually all famous Russian writers helped to justify Russia’s imperialist policies, promoted Russian exceptionalism or excluded the voices of oppressed nations. For many years, this literature has shaped how the West viewed Eastern Europe, Central Asia, and Baltic Countries. The culture of those people was often completely ignored in the face of “great Russian culture,” and their actual history — neglected, while Russian one was studied and glorified.

Unlike in other known empires, in the USSR and the Russian empire, and now in Russia no work has been done to recognize their imperialist past and present and counteract it. From the incredibly popular comedy TV series “My Fair Nanny” that ridicules Ukrainian culture to constantly using ethnic slurs for almost every single ethnicity, the imperialist mindset is alive and well in Russian culture. Such ideas are reflected in Russians’ attitude to their former colonies that they consider worthy of respect only if they cooperate with Russia. For example, it is a well-known social phenomena that many Russians in Georgia, Kazakhstan, Kyrgyzstan or Belarus refuse to study the local language and get resentful if not addressed in Russian.

Russia’s imperial ambitions towards its former colonies have already resulted in Russia’s wars in Chechnya and occupation of Ukrainian (in 2014) and Georgian territories (in the 1990s and 2008) and eventually has led to the full-scale invasion of Ukraine that started in 2022. The overwhelming support of Russians for the invasion comes from the prevalence of imperialist ideas such as that Ukrainian people (being “less educated”) need the help of Moscow to succeed. Being used to the image of stupid, caricature Ukrainians or the idea of “brotherly” relationship between Ukraine and Russia, Russians struggle to comprehend that their former colony can actually exercise its right of self-determination and not accept Russian “help” with open arms.

The West has turned a blind eye to Russian past and modern imperialist policies for centuries and now has to deal with the consequences. Without recognizing and counteracting the Russian imperialist mindset, we can not hope for the cultural revival of the subjugated nations within Russian borders or for political independence of Russia’s former colonies.

While the Slavic departments of American universities keep centering Russia at their course offerings and research, the culture and history of former Russian colonies will continue to be disregarded. If high school World History curriculum or college courses about colonialism continue avoiding the topic of imperialism in the Russian empire, the USSR, and modern Russia, Americans will keep falling to Russian propaganda and being “surprised” at Russian chauvinistic views.

Instead of idolizing Pushkin or Tolstoy, obsessing over Russian culture or praising Soviet leaders, Americans should educate themselves on Russian imperialism, critically analyze what they think they know about Russian history or culture, and amplify the voices of formerly subjugated nations. Only this way can they counteract imperialism around the world and help create the platform for all the nations colonized by Russia.