Behind the fourth wall

Please note: This article contains references to binge drinking, sexual assault, and bullying, which may not be suitable for all readers.

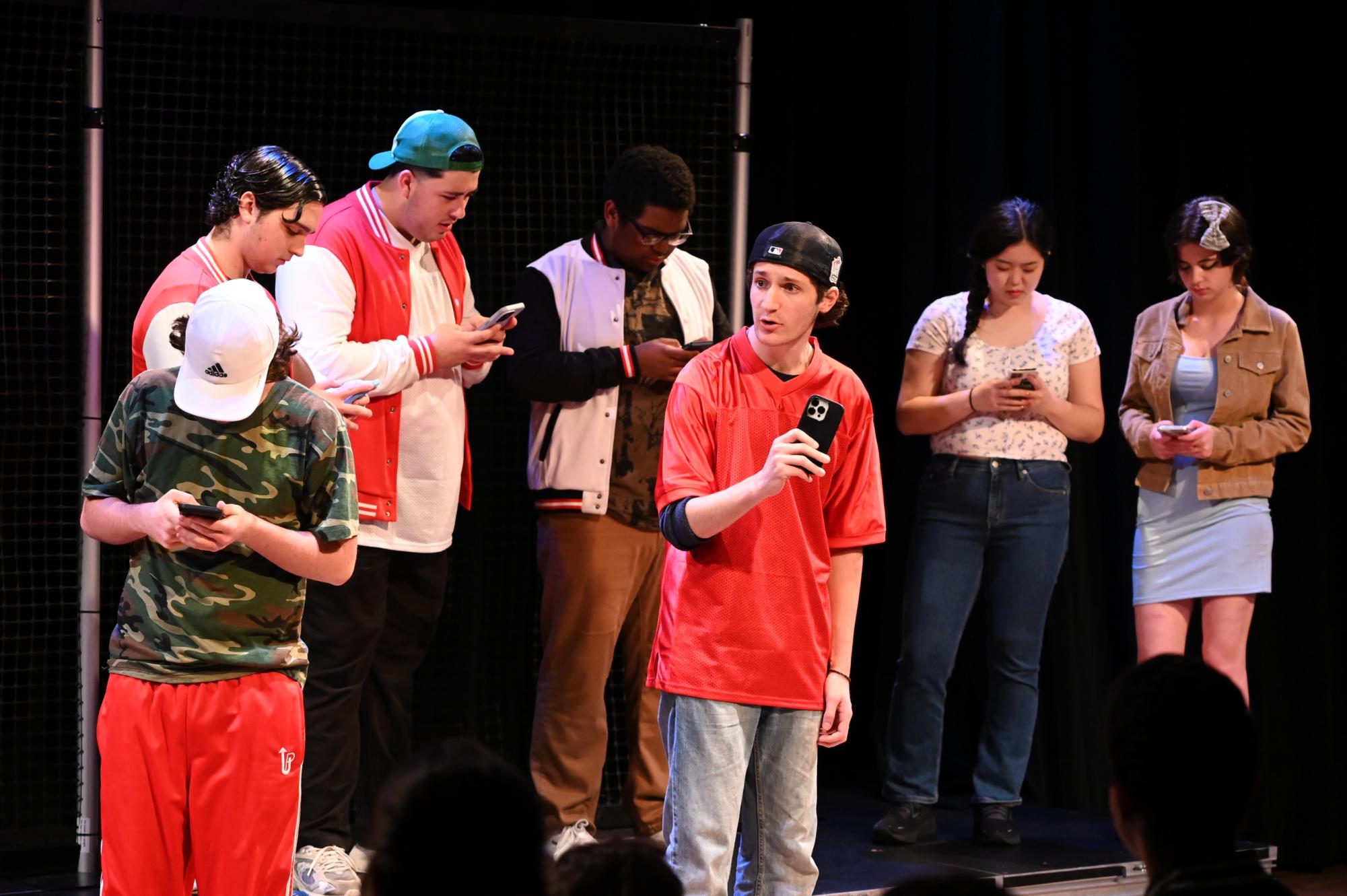

Mainstage took on dual challenges this fall season, tackling two plays at once, including one that tackled issues ranging from binge drinking to sexual assault. Last June, actors from the classes of 2024 and 2025 auditioned for Good Kids by Naomi Iizuki, which premiered on Oct. 12 through 14 in Masters’ Experimental Theatre. Taking on this project was new in two unique ways for actors: the casting and rehearsal timing, and the psychologically difficult content of the production.

Unlike previous shows, the majority of memorization work for cast members took place over the summer. Actors were given scripts following their June casting and memorized lines over the summer. This summer work was not done alone, however. Actors met over Zoom several times to read through the script together, discuss memorization tactics and more.

Actor Allison Tarter ‘25 spoke about the experience of summer text work. She said, “In June, I got fully memorized. I would sit down for 30 minutes once a week, and review and refresh, so that I knew that by the time I got to the end of the summer, it would be in my long-term memory.”

“I think it helped that from the very beginning of the process we understood the weight of this material. [The Zoom meetings were] a really supportive space, and I was really happy that we had time to run lines with each other and hear other people’s voices — it was really helpful.”

Good Kids was not the only play that went up during the fall. Mainstage production Trap, which followed the traditional fall play timeline of preseason auditions and a late October performance, was rehearsing simultaneously. As a result, Good Kids met less frequently during September — only two to three times weekly.

Every Wednesday, the Good Kids cast met with director Meg O’Connor to rehearse large group scenes and refine staging. Certain actors would meet and rehearse one to two additional days each week. These student-run rehearsals were called “Captain’s Practices,” where actors received guidance from O’Connor on what to work on while she was not there.

Tarter said, “We took [rehearsals] really seriously. To us, it wasn’t a co-curricular, it wasn’t something we were doing outside school — it was something really important that we were doing.”

“We took it more seriously because we all understood that this needed to be accurate and believable. The play is written so poetically that it’s easy to make it fall flat, so we had to get really specific with the script analysis.”

Approaching a show with heavy content including sexual assault was new to actors, and maintaining their physical and mental safety during the show was a top priority. O’Connor implemented several strategies for actors to disengage from the characters they played during the rehearsal process.

The first was called “kit” — an all-black uniform actors changed into to mark the separation between themselves and their characters at the beginning of each rehearsal. At 5:45, the cast symbolically changed out of their kits, marking the end of rehearsals and returning together as a group of student-actors, not characters.

Actors used kits as tools to help them fully engage emotionally. Tarter said, “There were a couple of rehearsals where we were really thankful to have the kits, and where we needed the kits so much because people were breaking down and having really large emotional reactions.”

As they returned together, the Good Kids cast launched into a ritual called “reinforcement,” where actors would go around and say one word they wanted to take away from the day, one thing they wanted to strengthen, or one moment they wanted to praise, remember, or recognize. This varied per rehearsal — sometimes, actors would say “cues” or “memorization” as something they wanted to work on, and other times, actors might say “love” or “company” as a reminder of the community and trust they’d built together.

These all constitute part of what Mainstage dubbed “de-roling.” In short, this term denotes removing one’s self from their role by whatever means necessary, allowing them to detach from the play’s content and return to their school and work routine.

While de-roling was emphasized after run-throughs and rehearsals, it took place throughout the practice itself, too. In the middle of big scenes, actors would take breaks to stretch together and open their metaphorical “doors of joy.”

Tarter explained, “[We] would place our hands on the top of our heads, and then lift our hands like a little trap door. We would speak in really high-pitched, comical voices. Phrases like ‘I’m just an actor, I’m just telling a story. I’m not the character I play,’ and things like that. That helped in the really dark moments, because the stupid voice made everybody laugh. It was a nice mantra to recite to ourselves in times when the show got really dark.”

In developing their characters, actors put lots of work into distinguishing their characters from themselves through physical choices. “I think all of us made a distinct effort to make our characters physically different — not only in our hair and in our makeup,” Tarter said. “I know Madison [Tarter’s character] had a fidget with these big, bulky earrings that I didn’t wear often. She would tilt her head in the opposite direction. She would stand different. I think just the physicality, in addition to the kits and makeup, helped us step out of our characters.”

In addition to an emphasis on de-roling and noting the difference between actors and characters, O’Connor made sure actors built trust and friendship between each other. Rehearsals usually began with acting games that required physical interactions, and the first few weeks of practice had time carved out to discuss physical boundaries and preferences with each other. For intimate moments such as stage kisses, actors took part in a dedicated intimacy training rehearsal to make sure they felt safe and comfortable throughout the whole process.

Mainstage did not take on production alone. On top of employing these rehearsal procedures, O’Connor spearheaded a partnership between the Dean’s Office, the Counseling Center, and the student-run club, Mental Health at Masters, to discuss production week.

Dean of Students Jeff Carnevale explained that he entered the process as part of a broader collaboration to tackle one central question. He said, “I came in just a few weeks [before the play], along with the counseling center and communications, just as the play was approaching a point of ‘Hey, we’re going to have an audience, how can we make sure that we are supporting all of our community as we grapple with difficult subject material?’”

“I was there to help coordinate and make sure the pieces were in place to be able to support students,” Carnevale continued. “We worked with the counseling center to provide resources, and to create some language around how we can communicate with the community that there’s some strong content.”

The Counseling Center, alongside Mental Health at Masters, aided in that discussion process. Counselor Stephanie Carbone expressed her gratitude for the involvement of the club throughout the process.

“This is a club that’s now seen as an advocate for the community and really about sharing information,” Carbone said. “The counselors and Mental Health at Masters came up with some resources to put in the program — like RAINN — and having people know that the counselors are a resource.”

In addition to distributing information and reminders, an advisor for Mental Health at Masters attended every performance. During and after shows, the club’s student representatives were stationed outside the theatre, offering hugs, conversations, and support to any audience members who needed it.

On a table, six bowls were set up, with labels such as “Love,” “Hope,” and “Heal.” A large container filled with smooth stones sat atop the table for viewers to place into the bowls, a tangible action to help them re-concentrate their post-show energy.

Following production week, Mental Health at Masters’ club leaders continued to hold talking circles for the community to come together during lunch and process their post-show feelings. Carbone explained why self-care and providing resources for actors and viewers was essential.

“For some, this [play] is more triggering than others,” she said. “You’re busy being high school students, doing all the stuff that you have to do, and then you’re doing the show, and then you’ve got your own emotions, and you’ve got to manage them. So taking care of yourself, seeking support, [are important].”

Audience members who saw Good Kids found the show impactful. Junior Skye Pearlman, who saw the show all three nights, said, “It was tough because, yes, it’s people acting, but it’s also a real problem.”

“The first time I watched it, the content was definitely surprising,” Pearlman explained. “During the show, there were moments that were really jarring, and almost a bit scary. Leaving the show, I was also feeling a little bit like, ‘Wow, this does happen with people our age, and it happens everywhere.’”

Carnevale suggested that theatre was a great medium to spark important discussions. He said, “That’s the beauty of theatre: it gives us this opportunity to really talk openly about things we don’t always do that with.”

“I’m hoping that this sparks opportunities for dialogue around really tough topics, and it brings to the forefront things that are really pressing and important,” he added. “If we can expand those conversations to beyond the production in safe and healthy ways, I’m all for supporting that.”

Tarter seconded this notion and said, “It was important to have real, live theatre. It was nice to do something that felt real, and see people have a reaction in front of my face that felt real.”

She added that this play was especially important for our community. “This kind of stuff still happens at our school,” Tarter said.

“Every weekend at parties, it still happens at our school. It still happens at schools that your friends go to, that your little siblings go to, that your cousins go to,” she continued. “It was really amazing to get to look out and see the faces of people that were actually being impacted by something.”

Tarter concluded, “It’s when problems like this fly under the radar, and become this secret nobody talks about but everybody knows, that kids get hurt. I’m really glad we did this show, as hard as it was.”

I had the honor of being an actor involved in Good Kids. Taking on a production with a quicker-than-usual turnaround time, less frequent rehearsals, summer homework — and especially poignant content for a community of high schoolers — took lots of trust, love, and hard work from actors and the adults surrounding us. But the ultimate reward — telling a powerful story with real-world implications, and inspiring audience members to approach these situations with a compassionate mindset and the courage to take action — was worth the effort it took.

The play Good Kids tackles issues including sexual assault, binge drinking, and bullying. If you or someone you know are struggling with any of these issues, the resources below can offer you information and support. For students at The Masters School, remember that the Deans Office and Counseling Center are in place to help you whenever needed.

Rape, Abuse & Incest National Network (RAINN) — Call +1 (800) 656-HOPE

Suicide & Crisis Lifeline — Call 988

Trevor Project (Suicide Prevention/Crisis Intervention for LGBTQ youth) — Call +1 (866) 488-7386