The wealthy often move through the complex world of legal disputes with surprising ease, exploiting tactics to draw out and deflect their trials, as exemplified by the ongoing challenges faced by Donald Trump in his recent $250 million civil fraud lawsuit. In addition to the serious allegations of inflating the worth of assets and falsifying financial records, attempts to derail the case have already occurred — such as when Trump attempted to sue the trial judge, Arthur Engoron, for alleged authority abuse before dropping the lawsuit 22 days later. It feels like there’s this secret playbook that allows the affluent to dodge, delay, and derail legal accountability — and the reason it feels that way is because there is one.

When wealthy individuals engage in illegal activities, their ability to delay consequences significantly helps them. Despite a widespread belief that they buy themselves out of trouble by hiring very high-quality lawyers, their actual strategy is much more corrupt. As Jonathon Wolf, an attorney at Rinke Noonan Attorneys at Law and columnist for the news website Above the Law, explains, “If you have the money to throw at a big law firm … you’re paying for them to throw money at the other side, whether it’s another giant law firm or whether it’s the government. I think it’s a war of attrition. It’s a resource war. It’s not that those lawyers are smarter.”

Hiring prestigious firms is not about getting great representation or legal intellect; it’s about paying for the firms’ time and ability to file countless motions to delay the trial and create pressure on the opposing side. Still, delays do not signify cancellation, and trials generally don’t have expiration dates, so why stall?

First, it reduces public pressure. Public sentiment plays a role as the public’s anger diminishes as time passes. The longer a case drags on, the less outcry there is to allocate tax dollars to it. Thus, affluent people can drag the trial out long enough to divert the spotlight off themselves, escape scrutiny, and potentially negotiate more favorable outcomes, such as reduced penalties. Second, filing more motions increases the chances of winning more motions. Wolf states, “Most of the motion practice you see is more for strategic gains here and there. You might file a motion to exclude a certain piece of evidence or to exclude a certain witness and thereby strengthen your case.” Although this approach also guarantees additional motion losses, the cumulative effect of these small wins can be significant.

Unfortunately, motion abuse is deeply ingrained in our legal system, with little punishment for those who exploit it. Wolf explains, “It’s almost impossible to hold lawyers accountable for just filing too many motions … that is standard practice for big firms.” Additionally, the effectiveness of the legal mechanisms to address this — such as Federal Rule of Civil Procedure 11, which permits sanctions against attorneys who submit motions for improper purposes — has been minimal in stopping the misuse of motions.

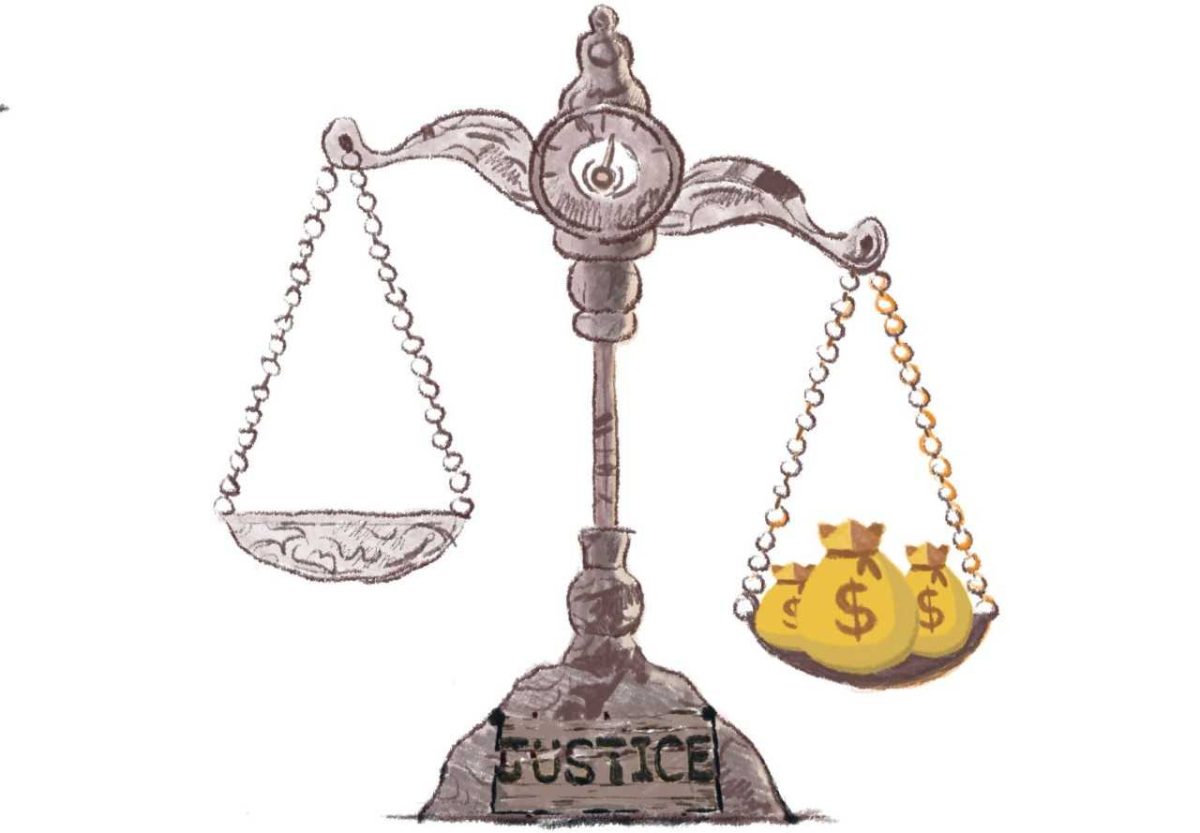

While the exploitation of motions is just one way the wealthy may avoid legal accountability, it is an example of a broader systemic issue that requires our attention. When the legal process should uphold justice, the advantage the wealthy have in delaying and derailing trials contradicts this principle. Manipulating the system that is the foundation of our society should not be a privilege granted by wealth. Overwhelming the legal process with countless motions, stalling proceedings, and blunting public outrage exposes a glaring loophole in our system. This is not just about one high-profile case; it’s representative of a systemic flaw. To address this issue, we must reassess our procedural rules, such as Rule 11, advocate for reform, implement more effective accountability measures for attorneys, and work towards securing justice and equity for all. Misusing motions isn’t just a legal tactic; it undermines public trust and obstructs justice.