The internet makes it easier to exploit children

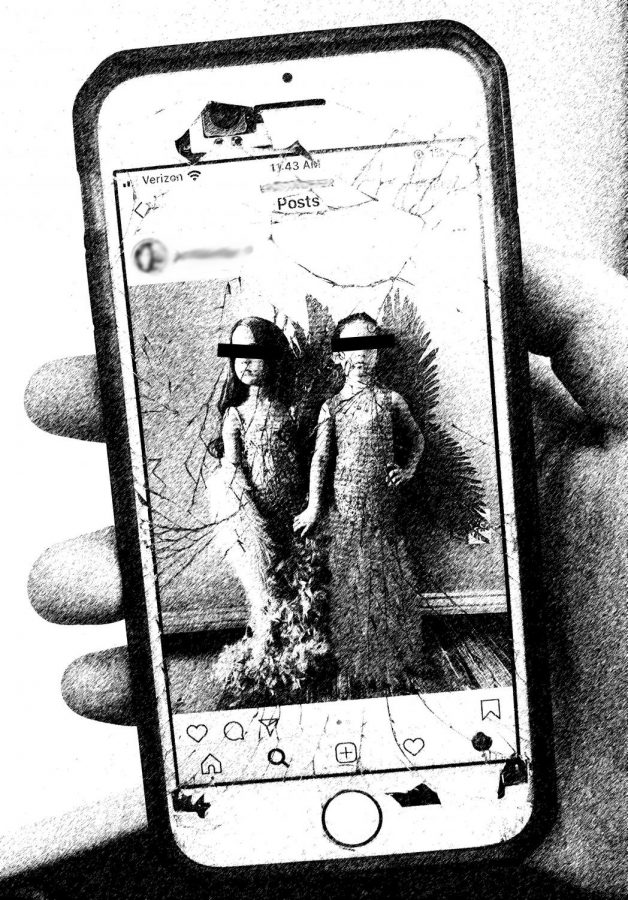

An influencer mom, with over three million Instagram followers, posed her two daughters in dresses mimicking Kylie and Kendall Jenner’s Met Gala dresses. The post amassed over 750,000 likes.

December 4, 2019

I don’t use Facebook often, but it takes only about two minutes of scrolling through my feed until I see a picture of a baby or a child. Cute? Maybe. Wrong? Definitely. Whether it’s a photo of a newborn immediately after birth or a post celebrating yet another milestone of the arduous kindergarten year, it feels wrong to me – and that’s because these young children can’t given consent to have their images posted.

There is nothing wrong with creating family videos and commemorating special milestones. My parents have hundreds of videos of my sister and me playing, getting our hair cut, or going to our first days of school; we’re lucky those moments have been recorded. But there is no reason for parents to post this content to the internet without permission – especially if they profit from it.

Children being professionalized (and too often sexualized) at a young age is not a new problem, it is just more common in the day and age of the internet. Child beauty pageants have been happening off-line for fifty years. Annually, 250,000 girls, some as young as two, are spray-tanned with makeup caked on, wearing sexualizing dresses and then given numerical ratings in competition categories including talent and swimwear.

In the pageant industry, children are expected to be conventionally attractive. In one episode of Toddlers & Tiaras, five-year-old Ava performs a cage dance in a midriff-baring outfit while being wolf-whistled at by judges and watchers. The message is clear: sexiness is her most valued quality.

JonBenét Ramsey is one of the most well-known child beauty queens. She performed in pageants all over Colorado, her home state, starting at the age of five. On Christmas day in 1996, the six-year-old was found dead. There was a ransom note found the night of her death, which was ruled a homicide. Although there was no evidence of rape, authorities determined that she had been sexually abused.

The case brought international attention to the inherent flaws of pageantry and child performers in general – how much of it is their choice? The Denver Chief Deputy District Attorney at the time, Karen Steinhauser, said “it’s impossible to look at these photos and not see a terribly exploited little girl.” Children in the public eye can only be protected so much; when they become famous, their privacy is gone. Even if they aren’t sexualized, they have their childhood, and all sense of normalcy, taken from them.

It takes a lot of time and effort to objectify, sexualize and profit from non-consenting children on the beauty pageant circuit. But the internet makes it much easier to exploit children. Some of that exploitation can seem as innocent as fun family videos. In 2018, the highest-paid YouTuber was a seven-year-old boy named Ryan Kaji, who fronts Ryan ToysReview. In these videos, he plays with toys and provides commentary; often these are sponsored by toy companies, but the channel fails to adequately disclose this. Although a separate issue, this is an example of how children’s content misleads kids.

Ryan ToysReview made $22 million in ad revenue, related merchandise and sponsorships last year alone. The channel has amassed over 30 billion views since he started posting to YouTube at only five years old. He is now being used in a television show, Ryan’s World. At age seven he has a full-time job. This isn’t innocent fun – this is exploitation. Maybe content on Ryan ToysReview began as a way to entertain other kids, but because of the channel’s immense profit, intentions seem to have changed; now that there is an economic stake in the game, ethicacy goes out the window. Children should not be global franchises. They should be children, free to explore and grow without the constant threat of scrutiny by the media.

On Instagram, it has become common for parents to exploit their children’s cuteness for “likes” and “follows” – and for money, as they are uploaded as sponsored posts, making money for the posters. The account “@vassylou.lou” uploads professionally-taken photos and selfies of Vassili, the account owner, and her daughter, Luna. Together, they pose in front of mirrors, often dressed identically. Sometimes, Luna wears designer tube-tops, sleeveless dresses and high-heels (often a few sizes too big: her heel doesn’t reach the back of the shoe). In a post uploaded on Nov. 13, Luna is staring into a phone screen that her hands can barely fit around. The selfie was sponsored by a children’s clothes designer, Amy Mode. Vassili’s account, with over 60,000 followers, is not an outlier on the platform. She posts under the “kids of Instagram” hashtag, which is full of child models and baby videos.

Beyond the questionable ethics of exploiting a child’s image for money without their consent, the seemingly innocent photos that Vassilli uploads also normalize the sexualization of children, just like beauty pageants. Her posts can be distributed, edited and encrypted. They can, and do, end up in the hands of pedophiles. The New York Times has reported extensively on the flood of sexual images of children that washes unchecked through the internet. Images like Luna’s serve as gateways to more lurid and illegal content.

Today, children have legacies on the internet before they can even say the word Google; they are not in control of their online footprints. Kids should not be exposed on social media at such young ages, along with its danger and hate. The moment an image is uploaded of a young kid, their privacy is compromised; once something is posted to the internet, it is out there forever, free for anyone to view and distribute. Even if the content is non-sexual, children can not properly consent to being on the internet.

Question what you endorse on social media and remember that childhood is an innocent, incorruptible freedom. Children cannot properly consent to being hyper-sexualized, especially for monetary purposes and social media popularity. That is the line between okay and not okay: intention. We cannot post or promote exploitative content; this is our collective responsibility and we must do better.