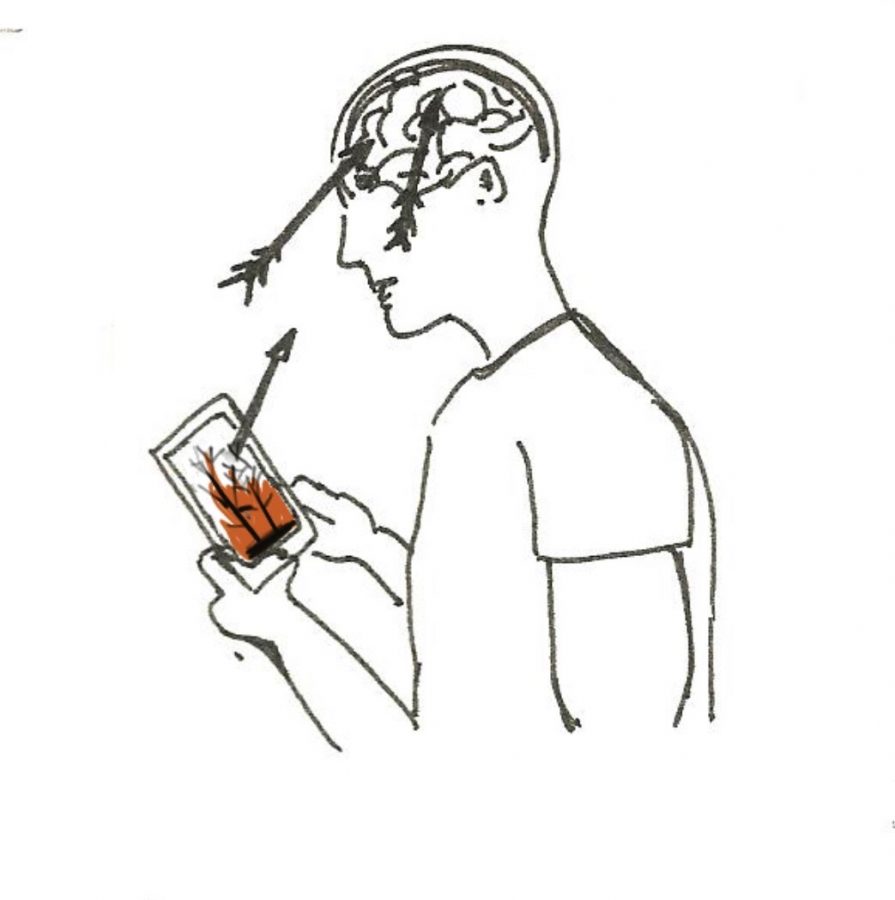

Social media creates an unhealthy reliance for Gen Z’s news consumption

Young adults and teens alike increasingly use social media as their main source of news consumption, but its potentially detrimental effects have raised concerns.

February 20, 2020

Junior Jason McGuire opened Instagram on his phone one morning before school early this January, and it was then that he first learned about Australia’s devastating bushfires – from a post by one of his close friends, rather than from printed news or news organizations’ website.

McGuire’s story is far from unique. In the wake of the decline of print news, news posted by individual users on social media sites has gained popularity. In 2019, 36 percent of Americans, aged 19 through 29 reported to have used social media for news in combination with more conventional media, according to a Pew Research Center study. And over recent years, that number has been climbing. As these posts gain traction and a new generation tunes in, the accuracy of their worldview is at stake and they are forced to wonder whether they can count on these posts to reliably shape their perception of current events.

The modern news anchor can be anyone with a phone and two thumbs to type. Sophomore Patrick Curnin-Shane considers this convenience for both the reporter and consumer to be one of the major benefits of social media.

“In a lot of circumstances, like the Hong Kong protests [2019-2020], speed has been amazing. They’ve [protesters] really been able to organize quickly,” Curnin-Shane said.

However, high speed can sometimes result in less accuracy. Sensationalistic headlines and buzzwords, which are commonplace on social media, often catch the eyes of users who have the ability to spread the news with the push of a button, without fact-checking.

Curnin-Shane said, “[Social media users] see something and just retweet or repost, and that’s why fake news can spread so quickly.”

Social media’s lack of accuracy is a concern for some, but many give it credit for providing baseline information to readers on current events that they would not otherwise know about.

Junior Tucker Smith said, “I think news from social media is definitely biased. It at least lets you get your news, but it definitely filters it through a specific lens.”

Junior Drew Zukerman said he’s also noticed bias on his social media news feed.

“Often, there’s a liberal skew, especially on Snapchat. Issues are not as clear-cut as they make it out to be,” he said.

The “lens” through which the news is filtered does vary: according to a different Pew Research Center Study, 48 percent of users generally notice a leftward lean on their social media feed, while 15 percent notice a rightward lean. The rest thought that the news on their feed was generally moderate.

This variation can be likely explained by one distinguishing factor of social media: its content is user-driven. While other media outlets, such as newspapers or television networks, are controlled by news conglomerates, the social media news narrative is controlled by the millions of individuals who release information. User-driven content is the lifeblood of social media, but it is the platform’s Achilles’ heel to some.

Freshman Jack Borwick said most of his news comes from individual social media users, and is often somewhat opinionated.

“People post their opinions and try to make you believe what they believe, which is not always what you should believe or what is actually right,” he added.

While some, like Borwick, fear being persuaded into something they don’t regard as true, others believe that social media news acting as constant reinforcement of already held beliefs may be a more pressing concern. With the push of a button, users can choose to see more of what they like and see less of what they don’t. Social media can become an echo chamber of repeated reinstatement of the user’s views – a potential breeding ground for extremism.

As industry giants like Facebook, Instagram and Twitter become more prevalent parts of our day-to-day lives, it becomes increasingly difficult to avoid social media news. But, these posts capture only one user’s voice and, consequently, only one angle of a story. Diversifying coverage of an event only broadens one’s understanding, as freshman Tyler Hack believes.

“I try to find articles about the news from both sides to see whether it’s credible,” he said.

Sophomore Olive Saraf said she finds that there are also several subtle cues that can indicate the credibility of an account.

“I check the page to see their bio to see how many followers they have, or if their posts are for one group of people, because then it’s probably not reliable,” Saraf said.

Others, like junior Maddy Ciampa, find it equally important to try to discern the motive of the poster.

“You have to try to figure out whether it’s someone doing it [posting] just for publicity or for a good cause,” she said.

The recent passing of NBA icon Kobe Bryant has illustrated the tendency of some users to post for publicity and likes rather than to serve the public. Shortly after the news of his passing broke, twitter user @OfficialKito posted a video of a helicopter crash with the caption, “#KobeBryant helicopter crash live footage.” The video quickly gained traction and was viewed by thousands. It was later discovered that the video was of an unrelated helicopter crash near Dubai in 2018.

As technology continues to alter the ways in which we consume media, many are finding that the Age of Information has made no promises of accurate information.

Junior Allie Koziarz said, “Getting news from social media can be hurtful because it gives us a false sense of reality. It makes us think that we are more informed than we are.”