Finals: A failed attempt at measuring student success

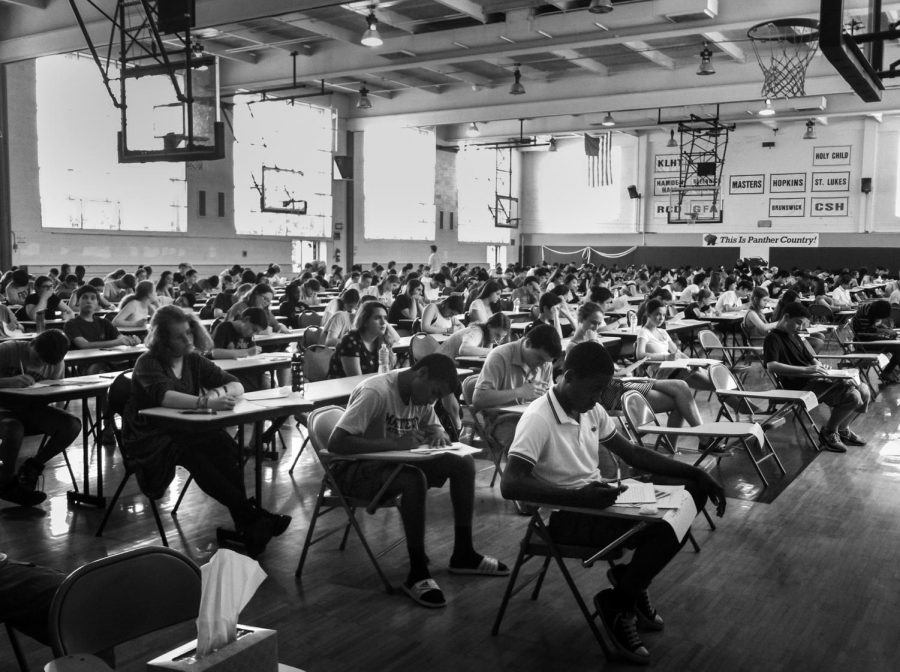

A group of students sweat out their last hour of their history exam in Strayer Gym. Although students did not take any final exams this past school year due to Covid-19, exams typically take place the last week of school.

February 8, 2021

At the end of the school year, students of all grades occupy every quiet space accessible, reading textbooks, reviewing tests, and consulting past notes, preparing for the ultimate feat: final exams. Although these tests are meant to assess the skills and material that students have learned throughout the year, the exams actually work against the teacher’s goal. They limit what students can learn. The solution to this problem is eradicating finals, and instead, asking students to work collaboratively on projects, where they are able to properly convey their knowledge.

Finals induce frantic and stressful studying, which has been proven less effective than project-based learning. When students engage in collaboration, self-confidence and creativity improve, teaching them the importance of critical thinking and leadership. This type of learning improves one’s awareness of their own thought process, or metacognition. However, if faced with projects in lieu of testing, students can receive feedback along the way, giving them an opportunity to improve.

When students take final exams, metacognition is impacted in a negative way because they aren’t given the opportunity to fix their mistakes and learn from them. After receiving report cards, they can only look at their finalized grade, unable to see what they got wrong on the test. Education often emphasizes the importance of learning from our mistakes, but in reality, final exams only teach students to avoid such mistakes at all costs.

If a student does well on a final exam, it is mostly because of their ability to memorize an ample amount of information in little time. The issue with rooting success in memorization is that students are not gaining anything from the class. This was observed by Cognitive scientists Daniel Willingham and Robert Bjork in a 2015 survey where they tested college students to see how much they could recall two weeks after the test. Two weeks went by and the students had forgotten more than 90% of the information.

Although many people argue that testing prepares students for the rigor of college, I believe we should instead send students off to university with knowledge of how to work with others and ask the appropriate questions, not simply recall a list of facts. In this day and age, many of the facts that we learn from a textbook can now be looked up online so we need to teach students how to problem solve and communicate with their peers, not memorize a list.

Around the world, high school students report that tests cause more stress than anything else. The Counseling and Psychological Services at Brown University noted that one of the most common scholastic impairments in our schools today is that approximately 16-20 percent of students have high test anxiety; an additional 18 percent struggling with moderately-high test anxiety. This means that when it comes to sitting down for an exam, students “freeze” or forget the information that they have studied when reading test questions. Regardless of how much information they have actually retained from the classroom, their high test anxiety has now reduced their working memory, increased their mistakes, and ultimately lowered their scores. According to the American Test Anxieties Association, students with this testing anxiety score about twelve percentile points below those who have low anxiety, which translates to about half a letter grade below. Should schools use high pressure, those with anxiety will continue to face challenges that test-based grading doesn’t account for.

At Masters, final exams are not only an annual occurrence but make up 20 percent of a student’s final grade for most year-long courses. This gives the exam heightened importance and only further communicates to students that their success in the course relies on this singular grade. High schools all over the country employ this type of grading system, which teaches students that doing badly on an exam discounts the effort that they have put in for the ten months prior.

We can’t continue to allow these exams to define our worth as students, and we do have the ability to make change. As it stands, our education system is more focused on how well we can perform in high-stress situations rather than what we have gained from the courses themselves. End of the year projects need to become the new normal, while anxiety-producing exams take a backseat. We have the power to shape our education and we need to take charge now.