The Ennui of Licorice Pizza

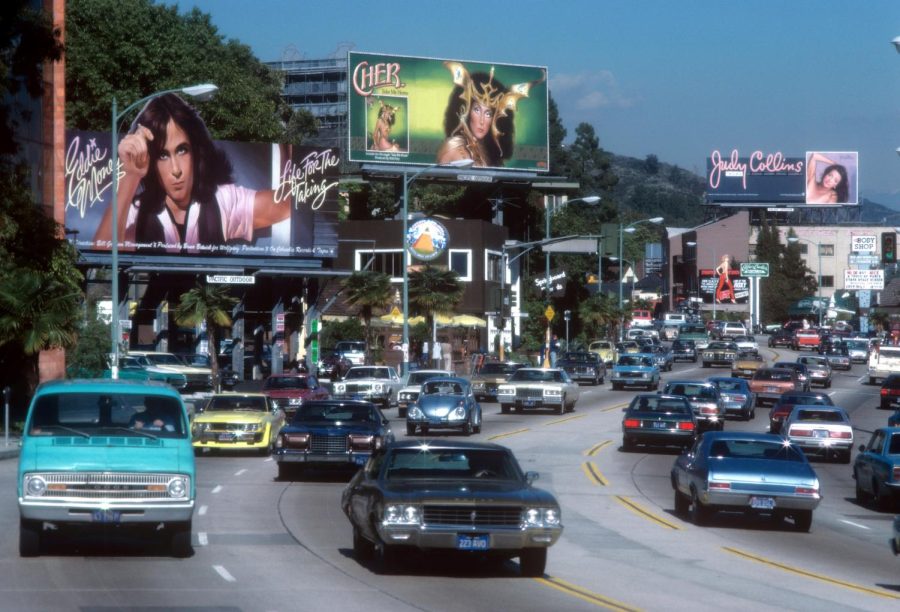

A Los Angeles highway in 1973, the year Paul Thomas Anderson’s comedy, “Licorice Pizza,” was set. In this coming of age film, protagonists Gary and Alana adventure through Los Angeles life, picking up odd jobs, meeting celebrities, and developing an intimate friendship in the process.

March 11, 2022

Something about “Licorice Pizza” resonated with me. The comedy is directed by Paul Thomas Anderson, known for his discordant dramas starring very-adult actors like Daniel Day Lewis and Julienne Moore. On the other hand, “Licorice Pizza” is a colorful period piece, a portrait of adolescence in 1970s California, and much less obvious in its conceit. Anderson’s previous films were heady and ambitious, but “Licorice Pizza” is ambling; he spends more time establishing a sense of setting and less time developing a forward-moving plot.

In fact, the film doesn’t aim to capture the protagonists’ growth. Alana and Gary, who are ten years apart, meet when Alana is taking yearbook photos at Gary’s school. In the film’s final scene, they run into each other’s arms, like at least three other moments in the two hour long film. This is not the fault of the characters (they did what they could, given the story they were written into.) Instead, the time period (both the 1970s and the stage of the characters’ lives) Anderson takes so long to delineate is the obstacle of the film that must be overcome: a permeating boredom and sense of paralysis in one’s circumstances.

What gives the film a distinctly 1970s feel is not Barbara Streisand, waterbeds, pinball machines, or even the clothing design, but the subtly and sparsely deployed political context. A mostly innocent film about adolescence is backdropped by rising gas prices, police brutality, and political apathy. We laugh when Alana and Gary run out of gas, but the ensuing sequence – a brilliantly-choreographed downhill roll in a truck full of kids that steadily gains speed – reflects most obviously Alana’s sense of crisis, but more ominously, America’s backslide.

Like the general malaise of the 1970s, the film dances around politics. Any references to current events exist not to make explicit commentary, but to characterize the life and movements of Californians at the time. There is a type of dramatic irony here – the characters’ apathy towards civil issues is like watching a car wreck – the audience knows where it’s going and can’t look away. When Gary is violently arrested by police officers then promptly released without so much as an explanation, he and Alana embrace then run through the valley. It doesn’t come up again. There could have been music playing in the background. Maybe the Bee-Gees. I don’t remember.

And that’s sort of the point – “Licorice Pizza” is like a stupor. Daze-like Hollywood dreaming. The plot isn’t so much one story, but multiple vignettes of life in the San Fernando Valley. But what connects these vignettes – the through line for a wandering film – is Alana’s experiences with the multiple men who exploit her. In the opening scene, Alana’s boss sexually assaults her. One of her romantic partners seems only to pursue a relationship for his own ego trip. (It doesn’t work out). She gets drunk with a much older, famous actor who literally throws her off a motorcycle and doesn’t recall her name. The mayoral candidate she volunteered for led her on with office flirtation, only to use Alana as his fall guy. In a film all about entering adulthood, it begs the question: what is womanhood, other than a perpetual game of dodging men’s violence (physical or rhetorical)? Even Gary’s relationship with her is a form of exploitation: he positions Alana within his own coming-of-age story.

The real center of gravity of “Licorice Pizza” lies in the interactions between these two characters. Their flirtatious relationship seems to be as much out of necessity as it is out of genuine affection. This is what the film does so successfully; it captures the ennui of early adulthood – the fear that there must be something better than Jimmy Carter, abusive men, dating boys who you have no business dating – and the immobility in the face of these truths.

“Licorice Pizza,” took me by the shoulders and put me in front of a mirror. Although it was an uncomfortably accurate portrait of my life stage, I left feeling validated in my roaming, my boredom, my restlessness.