How diverse is your AP class: The equity gaps in advanced classes remain prominent in the US

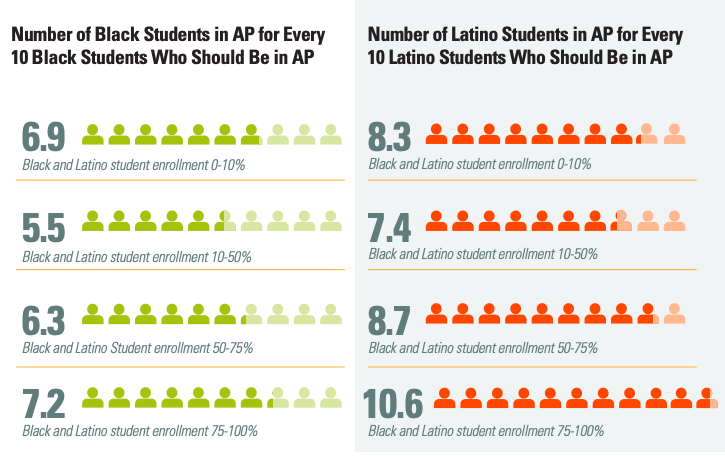

According to the report from the Education Trust, even in schools that offer AP classes, Black and Latino students are underrepresented. In the racially diverse schools, where Black and Latino students make up 10-50% of the student body, there are only 5.5 Black students and 7.4 Latino students for every 10 that should be enrollled.

May 1, 2023

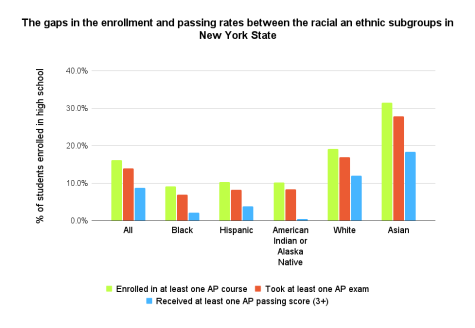

Black students make up 15% of high schoolers in the US, yet only 9% of students enrolled in at least one AP course. Similarly, 25% of high schoolers are Latino, but they make up only 21% of students enrolled in AP courses. Even among the schools that are racially diverse and offer an array of advanced courses, Black, Latino, and Indigenous students are underrepresented in AP classes. From the teacher and assessment biases to funding gaps to non-inclusive requirements and curriculums, many factors make it much harder for Black, Latino, or Indigenous students to enroll in, take, and then pass an AP class.

Benefits of AP classes

Despite various limitations of the AP curriculum and its focus on final exams, many students choose to take AP courses as a way to boost their college applications and show their academic abilities. Moreover, AP students get to challenge themselves and prepare for the more rigorous college classes. If one’s university recognizes college credits earned in high school, AP courses make it easier for students to take more advanced classes in college, double-major and graduate earlier. With enough AP classes taken during a high school career, one might save money on tuition for at least one semester of college, considerably lifting the financial burden off their families.

Lack of AP offerings in schools

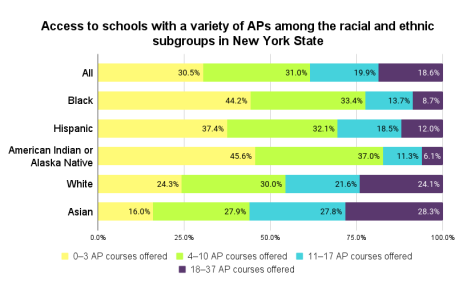

Yet, not everyone gets to reap the benefits of advanced classes. One of the main reasons behind the alarming statistics is the lack of AP course offerings in the schools that serve predominantly Black, Latin0 or Indigenous students. For example, 35.3% of American Indian or Alaska Native students enrolled in public high schools go to schools offering zero APs as compared to 14.8% of all students nationwide. The obvious solution to this issue is better funding. By allocating more dollars to teacher-training opportunities, curriculum materials, and technical assistance, the school districts can expand the AP offerings and help meet the student demand in all of the schools in the area.

The data was adapted from the 2015-16 Civil Rights Data Collection and the Center for American Progress report “Closing Advanced Coursework Equity Gaps for All Students.” (Viktoriia Sokolenko)

Masters with its 15 AP class offerings can also benefit from expanding the variety of courses offered. Esperanza Borrero, Associate Director of College Counseling, said, “Here at Masters our AP courses are STEM-heavy. So when you’re a STEM student, you have a lot more AP courses to choose from than if you were humanities, because all we have are AP languages, history and English. We’re not offering psychology, economics, world history, geography. And so like, if you expand that, you might actually incorporate more people into it.”

Support for students during the sign-up process

Suppose the school does teach AP curriculum, the wide choice of advanced courses does not guarantee equal representation in those classes. According to the 2015 survey from U.S. Department of Education’s Civil Rights, only 18.5% of Black students studying in the schools offering 18-37 APs were enrolled in at least one of those classes as compared to 30.1% of all students in those schools. Similarly low numbers (23.3% and 25.5%) were found for Latino and American Indian or Alaska Native students respectively. The equity gaps evident from this data are the results of various factors preventing students from underrepresented groups from taking the available AP courses including the lack of diversity among teachers and students, few resources for preparation, and the overly limiting prerequisite requirements.

On their way to improve the access to advanced classes, schools can start off by engaging student families in continuous conversations about program availability, its potential benefits, and fee waivers or financial aid available. If the family’s home language is other than English, communication in that language would make it much easier for them to navigate the course selection.

“What we see is that if you might be coming from a family where you’re a first generation college student, your family’s background might not have discussed this during their education.” Borrero said. “Or if they hadn’t gone to college, they might not have understood or know exactly why you’re trying to take college credits in high school. And so that conversation isn’t happening as often if you’re a first generation student, which puts you at a disadvantage.”

The costs associated with taking an AP exam can also shift the families’ decision. To reduce the barriers to enrollment, some states offer discounts to families unable to pay for the exams or provide fee waivers. At Masters, the student’s financial aid is applied to their test cost.

Biases in student identification

Oftentimes, however, the student’s willingness to sign up for the course is not enough. It is up to their teachers to approve the request. Most schools rely on the recommendations from the counselors and teachers to evaluate students’ academic abilities, without accounting for the faculty’s possible implicit or explicit biases. Several school districts in the country have tackled this issue by implementing automatic enrollment policies. For example, in Federal Way Public Schools District in Washington, students from grades 6-12 are automatically enrolled in the highest available course if they meet the benchmark proficiency levels.

“Some of the interventions that some school districts have done is the default class is AP,” Borrero said. “And so like, if you’re going into 11th grade English, everybody is enrolled in AP English Language. […] And it’s not for you to advocate for yourself to get into an advanced course, the assumption is, you can do the advanced course. And then if you don’t want to take that course, you can elect out of it.”

Transparency of request and enrollment process

Another way to support students from the underrepresented groups is to make the request and enrollment process more flexible and transparent. Usually, at Masters, after a student requests an AP course, the department decides whether or not to approve this request. For each department, there is also an appeals process, which often involves talking to a department chair. Many students, however, are not even aware that an appeals process exists, not to mention when it takes place and in what form. Gifty Baah’25, who plans to take 3 AP classes next year, said, “There’s still a lot I don’t know about the AP course process, and I do wish there was more transparency surrounding the process, appeals, and general experience.”

One of the initiatives started this year aims to tackle this problem. This month the school sent out a survey to students and faculty about what they know about requesting a course, getting it approved and potentially appealing the decision in an effort to create transparency around the process and support students who want to take advanced courses.

Preparation for AP classes

The data was adapted from the 2015-16 Civil Rights Data Collection and the Center for American Progress report “Closing Advanced Coursework Equity Gaps for All Students.” (Viktoriia Sokolenko)

The underrepresentation in AP classes is a result of many bigger systematic issues. Who gets to take an advanced course in high school largely depends on who got to take advanced classes in middle school or got placed into a gifted program in elementary school. In many cases, it is the children from white and/or middle-class families who start taking higher level classes at a younger age and, thus, are considered more qualified to take those classes later in high school. Universal screening for gifted programs, already implemented in some districts, can make it easier for students to get access to advanced courses throughout their elementary and middle school career. In the FWPS district, for example, not only all the students are screened for talented programs in early grades, those programs are also designed to be accessible and close in distance to students’ homes. Similarly, by aligning the standards for competencies and skills students should obtain from the first grade to their senior year, the school districts can ensure that more students are prepared to take and more importantly succeed at advanced classes.

Finally, to encourage more students to enroll in AP courses, the schools should provide the resources and support they need to succeed. Some of the initiatives Masters may consider borrowing from other schools may include peer tutoring centers, expanded office hours, or even professional tutors assigned to students.

Need for school interventions

Amaris Asiedu ’23 said she was very lucky to have a lot more people of color in her AP Literature class as compared to the predominantly white AP Environmental Science class she was in last year.

“In AP Lit [representation] is especially [important] because you have to talk about books like “Beloved” and “Americanah”, and a discussion flows more easily because now there’s people who can actually relate to the book,” Asiedu said. “So it’s not just [white students] saying what they think and maybe saying something ignorant. It makes it so much easier [for me] to talk about certain topics, and it also allows for other people to learn about things they may have not learned about before, about other people’s experiences.”

Asiedu’s experience in AP Lit class should be a normal occurrence, rather than an exception. Expanded course offerings, supportive teachers, easy-to-navigate course selection process, and accessible opportunities for preparation to higher-level classes are just one of various interventions that school districts and independent schools have already started implementing to tackle the inequity in the advanced classes. Masters should learn from those examples and catch up with other schools in implementing systemic changes to its curriculum and approach to teaching.