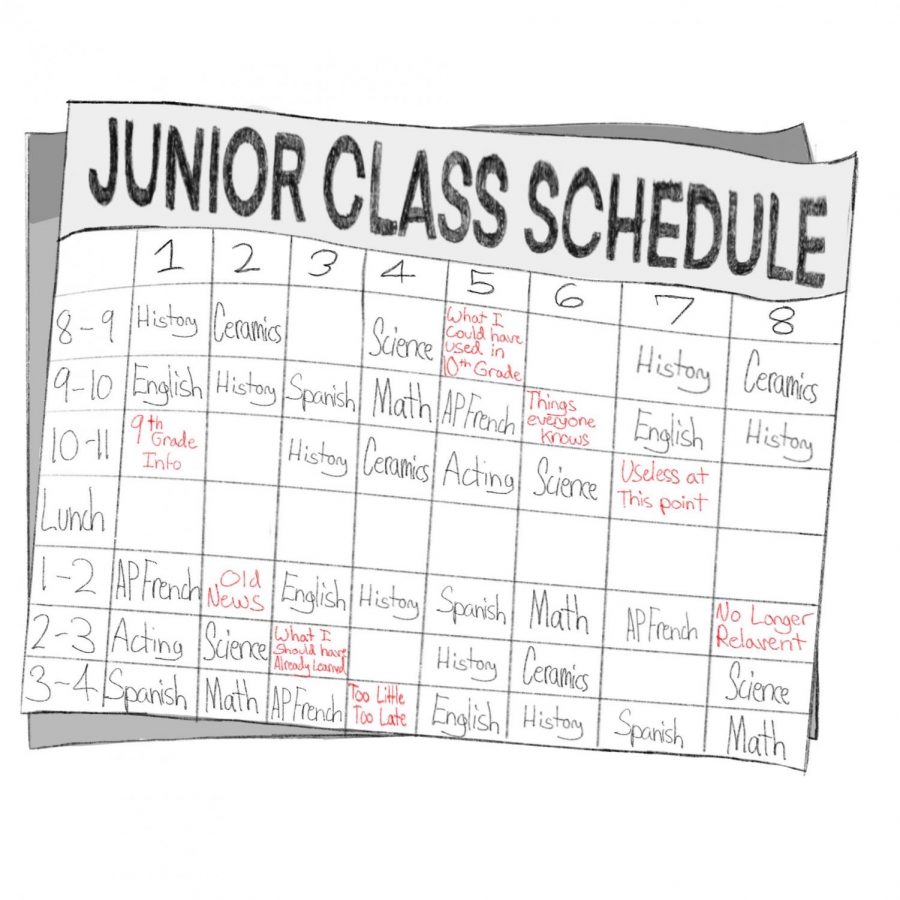

11th Grade Drug Education: Too Little Too Late

Health class, mandatory for all Juniors, is a valuable part of the Masters curriculum and provides crucial drug education to its students. Leo believes, however, that its efficacy is stifled by not offering the class in an earlier year.

December 18, 2019

From the D.A.R.E. era of the 1980s to the present day, drug use has been a problem at the forefront of many school administrators’ minds, and Masters is no different. We, like the vast majority of the country’s schools, have an irrefutable drug problem that desperately needs a solution, not only for the well-being of the users, but that of the entire student body.

Many of the factors that may contribute to the Masters drug problem are difficult to control, whether it stems from the students’ upbringing, mental health or the school’s wide-scale drug culture. But one solution is lying right under the administration’s nose: the school’s drug education curriculum.

Most of the Upper School’s drug education is taught in health class, which is mandatory for all juniors. Drug education programs, as reported by The National Drug Research Institute, do stop or delay the development of drug abuse. Our health class clearly has the potential to be an impactful solution to our drug problem: of the National Institute on Drug Abuse’s set of principles that the organization maintains that all effective preventative school programs should follow, the vast majority are covered in our health class. Despite an evidently well-planned drug education curriculum in health class, its potency is diminished by not offering the class earlier.

According to Dean of Students Jeff Carnevale, the class was slotted into the 11th grade curriculum mainly because of how well it worked with the mechanics of the schedule. However, health class should function as a preparatory class that gives students the tools and knowledge to make smart, healthy choices. Taking the class more than halfway through our high school careers, juniors are left wondering why they are only now being given this information.

The reality is that students do start experimenting with drugs and alcohol well before junior year. In fact, according to The National Survey on Drug Use and Health, some children begin abusing drugs as early as ages 12 and 13, making ninth grade the ideal year for intensive drug education in high school.

Though Ninth Grade Seminar does touch on drug-related topics, it does not cut deep enough into the subject. The class, while informative as it relates to protective factors and building drug resistance skills, lacks emphasis on addressing drug use risk factors and the specifics of all forms of drug abuse.

Furthermore, swapping the placement of health class and Ninth Grade Seminar would be in everyone’s best interest. Freshmen would receive the “high school preparation” class and a standardized base of knowledge on drugs and alcohol, whether they matriculated from the Masters middle school or elsewhere. Juniors, on the other hand, would certainly benefit from the discussion-based format of a seminar, which they could use to relate their experiences with drugs and alcohol midway through their high school experience.

The pride that the administration takes in the strict zero-tolerance policy for drugs and alcohol should also motivate change. The emphasis put on drugs and alcohol in the Family Handbook should be uniform to the emphasis put onto the importance of drug education in our curriculum. With any discrepancy, our drug policy becomes unfair; there cannot be an expectation for students to follow such firm drug policy without a proper drug education at the start of their high school career.

After the incidents of this year, there has never been a more pressing time for change. Before we forget about these events, let them serve as a wake-up call for what can we be doing better as a school.