Twists and turns on the road to a Covid vaccine

December 22, 2020

The forgotten history of vaccination

Childhood used to be far more deadly than it is today. A little over a century ago, the infant mortality rate in the United States stood at a staggering 20 percent, and the mortality rate for children aged five and under was also at 20 percent, as compared to the current U.S. infant mortality which stands at 0.57 percent. Among the leading causes of death in children at the time were measles, diphtheria, smallpox and polio. However, these diseases now feel as if they belong exclusively to the past, with little to no incidence in the U.S., they have been almost entirely eradicated due to widespread vaccination.

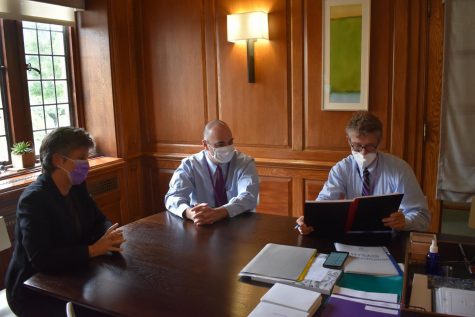

Richard Bruns, a Senior Scholar at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and an Assistant Scientist in the Department of Environmental Health and Engineering at the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health spoke to Tower and emphasized the importance in recognizing the indispensable nature of vaccines.

“[Vaccines] have such a long history of working, they’ve saved millions of lives all over the world and it’s kind of a weird, rare privilege that we have allowed ourselves to forget just how deadly childhood was in the past and how much vaccines have saved us from that.”

The documented history of vaccination begins with Edward Jenner, an English physician, who in 1796 developed the first vaccine for smallpox. Jenner’s accomplishment was revered by European leaders, and vaccination quickly grew to become an integral part of national pride, public health services and productivity in Europe and North America in the nineteenth century.

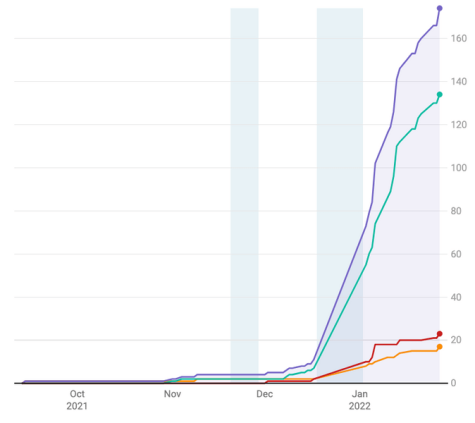

In more recent history, vaccination technology has been rapidly evolving since the mid-20th century, when researchers began to focus intensely on developing vaccines for childhood diseases. And now, in December 2020, vaccination weighs heavily on everyone’s minds.

Vaccine OK’ed for 16-year-olds; but teachers will receive doses first

School-age populations are among one of the last groups in line to receive any approved COVID-19 vaccine, and so questions of vaccination mandates in schools remain unanswered. Currently, there is no national mandate requiring vaccination for children to attend school, those decisions instead fall to the state-level governments.

Several of the COVID-19 vaccines have been put through Phase 3 clinical trials, but the vaccine has yet to be fully tested on children. Pfizer, a biopharmaceutical company, in collaboration with BioNTech, engineered the vaccine that is currently being administered in the United Kingdom. Teenagers as young as 16 were introduced into the clinical studies for the Pfizer vaccine in September, and adolescents as young as 12 in October. Moderna, another drugmaker that has developed its own vaccine, announced on Dec. 2 that it would begin testing its vaccine in children ages 12 through 17. The results of these studies have yet to become widely available and most trials in children are still underway.

The exact inoculation timeline is unclear. The efforts required to successfully produce and distribute millions of vaccines across the U.S. will undoubtedly be staggering due to the extremely cold temperatures at which the dosages must be stored and the mass scale of vaccination, but there is no concrete estimate of how long it will take.

Bruns said, “We’re hopeful that between all the vaccines getting approved there will be enough for the next school year, but it’s not guaranteed if there’s any kind of production or distribution issues, or if everybody in the older group decides they do want it, then by July or August, there may not be enough to vaccinate children.”

New York State has yet to release any vaccination mandates for schools, and so no determinations regarding Masters Covid vaccination policies have been made. The school would be allowed to require vaccination for all those on campus as a part of its own health and safety measures, but is unlikely to do so in the near future according to Director of Health Services, Sue Adams.

“We would definitely meet with the Health Advisory team if we were going to do something not mandated by New York State and make a decision about doing it for Masters, so I don’t foresee anything like that happening right now just because we don’t have access,” she said.

Vaccine approvals have varied from country to country, posing a serious challenge for international students hoping to return to school in the spring. Adams emphasized the uncertainty and possible danger in requiring a vaccine in people who have already received another drug.

“I’ve had some very interesting inquiries from our international families. Students from China have already been vaccinated in their country and if New York State says this is what we need to have and it is not the same vaccine, is it safe to give them two? We don’t know.”

In front of the students in line to receive the vaccine is the faculty, the second most populous sector of the Masters community. While children certainly can contract and transmit COVID-19, teachers are generally considered at higher risk for health complications if they contract Covid because they are older. If all adults in the community were to be vaccinated, Bruns said that would significantly weaken any case requiring that the students be vaccinated.

Adams echoed that sentiment. “It depends on the age of the teachers and what risk category they fall into, and I don’t know what the median age of our faculty is, but that certainly would be wonderful,” she said.

Vaccine developed swiftly but with safety in mind

US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Director Dr. Robert Redfield accepted the committee’s recommendation to begin administering the Pfizer-BioNTech Covid-19 vaccine to people ages 16 and older. This long-awaited approval followed the meeting of a Food and Drug Administration (FDA) advisory committee on Friday, Dec. 11 to determine whether or not to issue an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) of the Pfizer-BioNTech vaccine.

According to the FDA, EUAs allow “unapproved medical products or unapproved uses of approved medical products to be used in an emergency to diagnose, treat, or prevent serious or life-threatening diseases or conditions caused by CBRN threat agents when there are no adequate, approved, and available alternatives.”

Concerns in regards to the safety of the vaccine have arisen, particularly after two healthcare workers who received the Pfizer vaccine in the U.K. suffered allergic reactions. British healthcare regulators have since advised that people with a history of significant allergic reactions should not take the vaccine. It’s important to acknowledge though that no vaccine or drug is ever completely free of potential side effects, but the vaccines have been thoroughly tested before any mass inoculation could take place.

Bruns emphasized, “[The FDA] are being excessively slow and careful so no one should have any doubts about the safety of the vaccine.”

He explained the rapid speed of vaccine development not as an indication that the drug was developed hastily, but rather that the bureaucracy moved much more quickly in response to the gravity of the situation.

“There’s the actual work that you do, and then there’s waiting for paperwork and approval. The actual work has taken exactly as much time with exactly as much care as it always does. You have clinical trials that take months, you have due diligence in your data analysis, it’s been done more quickly because the bureaucracy has just moved faster, as it should. I personally think it took too long.”

Ensuring equitable distribution in the U.S.

Americans with Medicare, Medicaid, private insurance, as well as the uninsured will be able to take the vaccine at no cost. However, the physical barriers to equitable healthcare in historically disadvantaged communities remain. In the case of the Covid, vaccination is made more logistically difficult by the fact that both the PfizerBioNTech and Moderna vaccines require two dosages to be administered 21-28 days apart, respectively.

Bruns said, “Mainly the obstacles are going to be in disadvantaged communities. For most middle and upper class school-age populations it’s a slight hassle that you have to get to, but for most disadvantaged populations that’s a lot harder to arrange.”

COVID-19 itself has disproportionately affected minorities in the U.S.

A 2011 study the Racial and Ethnic Disparities in Uptake and Location of Vaccination for 2009-H1N1 and Seasonal Influenza by the National Institute of Health (NIH) observed that, “Epidemiological data collected over the past century suggest that racial and ethnic minorities are at greater risk of contracting seasonal and pandemic influenza—and of experiencing more negative consequences as a result—compared with Whites.”

Despite this increased risk for contraction of viruses, the study also found that minorities in the U.S. have historically “been vaccinated for influenza at rates as much as 15 to 18 percentage points lower than the rates for Whites.”

Bruns asserts that careful and intentional public messaging within typically disadvantaged communities will be essential to reducing major inequities in vaccine distribution.

“It’s important to understand that a lot of different populations, and various communities, who feel like the government hasn’t looked after them in the past, don’t trust public health messaging. And a lot of populations do have legitimate reasons for not trusting the government or thinking that the orders are just to benefit somebody else and not them,” he said. “It has to be a message that it’s not a bureaucrat telling you to do something, it’s something that you’re doing for your friends and your community.”

In the wake of the Black Lives Matter protests that swept across the country following the police killing of George Floyd in May, these issues of inequity have been given comparatively more attention within the medical community than years past.

Although the majority of Masters’ population will face little difficulty in being vaccinated when the time comes, Adams said that for those who vaccination is made more difficult by personal circumstances the school would make every effort to assist them.

“Certainly if there was a push to offer this at schools to get more people vaccinated, I know I would be supportive of that and that would have to be a discussion with our Health Advisory team.”