Reflection: Watching football brought me and my dad closer together

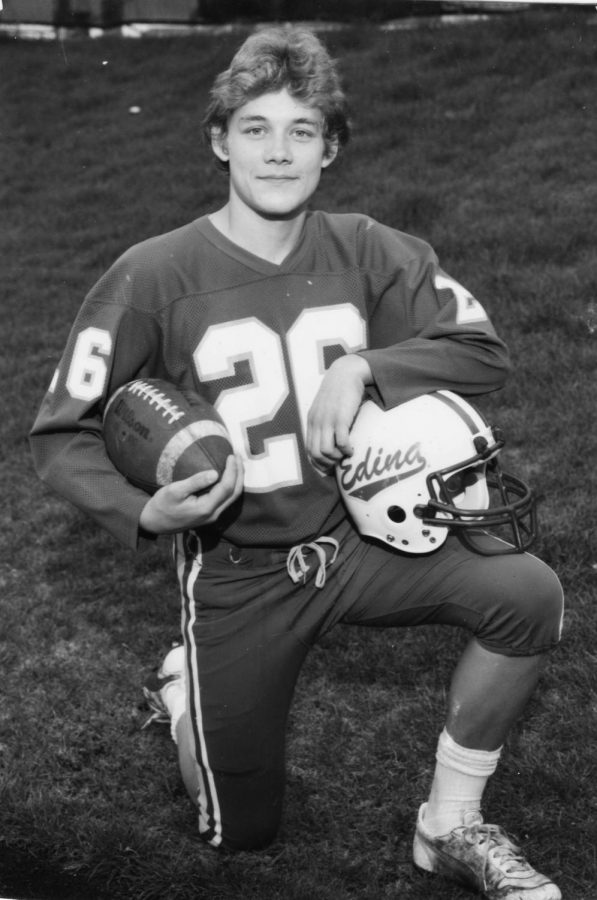

Gregory Van Beek grew up in Edina, Minnesota and has been a lifelong Vikings fan. He played football throughout middle and high school, and now he enjoys Sunday afternoons watching NFL games with his youngest daughter.

February 5, 2021

When my father was a sophomore at Southern Methodist University in the fall of 1988, he walked onto the school’s football team. A week later, he quit. The two-a-day practices in the blistering Texas heat weren’t worth the fantasy of a college football career at a disgraced football program, which had been banned from playing for two years after receiving the NCAA “death penalty” following a scandal involving illegal payments to players.

For almost my entire life, I had no interest in watching football. I didn’t know the difference between an extra point and a field goal until this past season. I don’t know what moved me to go downstairs one Sunday to watch the Vikings-Packers game with my dad. I told him I needed a win, or something to root for. After months of a growing distance between us, I think I just wanted to reach out to him. This game was important to my father, and so it suddenly became important to me.

The past several years, for as long as my family has lived in New York, my dad has put on his lucky #38 Minnesota Vikings jersey and watched every single game by himself. When the Vikings lose – which is more often than he’d like – I watch him sink into the sofa cushions in disappointment.

He’s been a life-long Vikings fan, but not by choice. (As my mother once put it, sometimes we are raised where we are raised). Tell anybody you’re a Vikings fan and they’ll cringe – memories of botched playoff games, overtime fumbles, or the roof of their stadium collapsing. Twice. (Never underestimate Minnesota snow).

But it’s a testament to my dad’s character that he puts his jersey on for every game, and tries not to get his hopes up, and continues to be a fan, without reservations, despite the agony and seemingly inevitable disappointment of rooting for the franchise.

It’s not that the team, with an 82-76 record over the last decade, is bad. Often, things just go wrong at the worst times, either due to questionable play calls by the coaches or plain old bad luck. My father still cringes when he recalls the 2009 (NFC) championship game. (For reference, the Vikings last went to the Super Bowl in 1977, when he was 8 years old). The tied game, which featured Minnesota and the New Orleans Saints, had been a back and forth contest throughout, and with less than three minutes left, the Vikings were driving for a field goal attempt. Then a flag was thrown because there were too many men on the field, and quarterback Brett Favre threw a heart-wrenching turnover to a Saints cornerback. Although the game went into overtime, my dad recalls that it was clear who the losers were straight from that interception.

By this December, I was fully committed to seeing the Vikings’ season through. Beyond becoming closer than my dad, I’d grown attached to Justin Jefferson’s touchdown dance, and Dalvin Cook’s powerful runs. Then came our game against the Tampa Bay Buccaneers, arguably a turning point in the season. Our kicker missed every extra point and field goal. It cost the Vikings 10 total points in a game we lost by 12, despite outplaying Tampa Bay in almost every other measure.

My father told me it was my first taste of that Vikings misfortune. He added that years of rooting for the franchise doesn’t make that feeling any less bad. We sulked back into our corners of the house.

As I’ve gotten older, the common ground between my father and I has slowly gotten smaller. Now, we have football. But it was never actually about the sport, of course. And while I’m probably more emotionally perceptive than him, I think he knows that, too. If it wasn’t important to my dad, I never would have spent a minute in front of a football game.

I understand my father better now. He’s a patient man, and doesn’t mind re-explaining the more complicated rules to me, like what an onsides pass is and the difference between holding and pass interference.

Recently, he’s been sending me tweets from his favorite account, Super 70s Sports, which I don’t really get, but still laugh at. It’s his way of reaching out. No matter how horrible our weeks were, or how I really should be spending my evening on homework, we both make our way to the living room, the smell of microwave popcorn and the sound of artificial cheers in an empty stadium, to watch his hometown team.

And I return to that image of a 19-year-old Gregory Van Beek (only two years older than I am now) walking wide-eyed into a college stadium and deciding that his love of football should be reserved for the living room with his daughter.