Where Masters’ DEI efforts fall short

Sophia Van Beek argues that the School must re-evaluate the way it approaches teaching race in the classroom.

November 29, 2021

In the days leading up to the Virginia governor election, which Republican Glenn Youngkin won, critical race theory (CRT) became central to the political landscape. Youngkin vows to ban CRT in public schools on his first day in office. This has led me to ask two questions: one, what even is CRT?; and two, how has race been taught in my school?

CRT, which has over 300 million hits on Google, examines the intersection of race and American legal, economic, and social institutions that perpetuate oppressive systems; this is a definition I have had to come to entirely through my own research, because I’ve never been formally taught this.

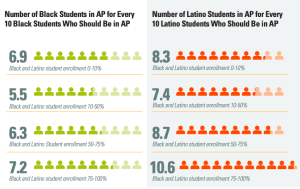

At The Masters School, an institution rooted in liberal curriculum and pedagogy, I believe that there is a serious lapse in what we teach about race and how we go about it.

First, let me acknowledge my unique position in making this point – I am a white person, in a primarily white institution. Anything that I write or think about race should not take precedence over the work of the Diversity, Equity and Inclusion department, or the voices of people of color at Masters. So instead, I intend to make a few observations and ask a few questions that, as a community striving imperfectly towards antiracism, we all ought to reflect on.

To begin, Harkness education, an approach so central to the School, is a flawed way to teach about race. Harkness emphasizes equality in the classroom and encourages all to bring a perspective to the table; in Harkness learning, students derive their own information through discussion, not lecture. However, there is some information that white students cannot derive about race, because we have not personally been victimized by individual or institutional racial oppression. When all opinions are valued equally, students leave the classroom thinking the correct answer exists somewhere in the middle-ground or is up for compromise.

This isn’t to say that offensive opinions and statements go unchecked in a Harkness environment; in fact, Harkness makes it easier to hold our peers accountable in discussion. However, as a primarily white institution, our discussion-based classes will always center the voices and opinions of white students. And while those voices and opinions might not be outwardly racist, they provide an incomplete picture of what is a very complex issue. The reality is, with discussions about identity, some voices do matter more than others, and the “correct answer” about oppression is always more accurate when based on the experiences and reflections of marginalized groups.

Beyond this, the curriculum within the humanities departments, which carry the burden of teaching about race, is not always aligned between classes, especially when students are given more choice for elective or advanced classes. Seniors in AP European History will learn about the ideological roots of race as a social construct as it emerged in Western Europe; a student who takes no history class their senior year will miss out on that essential lesson. And as much as I loved AP U.S. History, we had a few hundred years of past to cover in order to prepare for the exam, so meaningful interrogation of racial oppression couldn’t be prioritized in the syllabus.

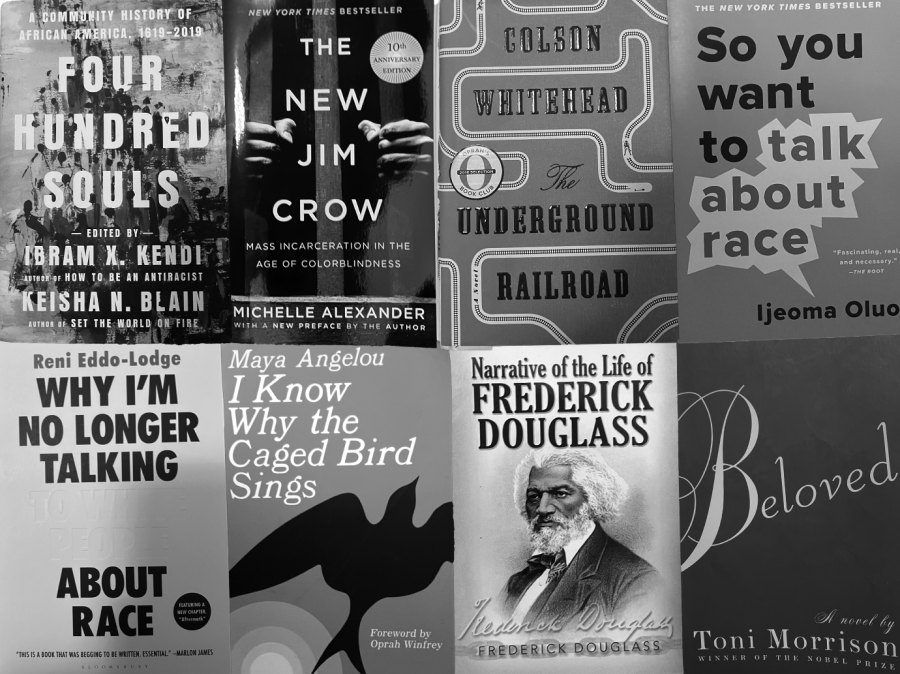

In my ninth grade English class, we read “I Know Why the Caged Bird Sings” by Maya Angelou, but that wasn’t true for everyone in my grade. In my current English class, I am reading “Beloved” by Toni Morrison, which is the most honest and unflinching depiction of American slavery that I’ve ever read. However, students in other 12th grade English classes will not have that experience.

In order to be true powers for good, Masters students need to leave the school having a thorough and nuanced understanding of race; we cannot do that if curricular development lacks coordination.

Lastly, we do way too much cushioning of students’ white fragility. For example, after being called out for a microaggression in ninth grade, my first instinct was to speak with Karen Brown, the former director of DEI, and hopefully be forgiven for what I had said; I wanted to be assured that I, in fact, was not racist. I have overheard students of color be told to “tone it down” because they might deter white peers from listening. Last example: white students are told to engage with discussions of race up until they do not want to anymore. The fact is, prioritizing and preserving white students’ comfort during discussions about race is just another way of prioritizing and preserving their whiteness itself.

In order to do justice to conversations about race, we need to think outside the traditional Harkness method of discussion-based learning. We should have outside speakers talk to the community about racial systems of oppression or watch documentaries like Thirteenth. This compels white students to listen rather than talk and also takes the burden off students and faculty of color to provide the “other side” during Harkness discussions.

Additionally, just as public speaking and health are requirements for graduating, we should have to complete a minor credit in CRT. Although there is a unit on DEI in ninth grade seminar, it isn’t central to the class’ mission – learning about race should not just be a unit or elective. Furthermore, upperclassmen are going to take away much more from a class on CRT than ninth graders, who don’t have the context of modern world history or US history.