Students quantify response bias in latest AP Stats project

Senior Carol Queiroz, who also did a project, polls fellow senior Hanna Frasca for her assignment.

February 3, 2023

If you’ve been on campus these past few weeks, chances are you’ve been asked to take a survey. Students taking AP Statistics have been collecting data for their most recent project, measuring different forms of response bias.

Research projects have sought to answer questions about the potential for response bias, such as whether the wording of a question, the provision of additional information, the characteristics of the interviewer, the anonymity of the respondent, manipulation/order of answer choices, or revealing other people’s answers to a questions could response bias.

The project began with the students designing their own survey. They asked questions such as “How often do you lie?” or “How do you use technology in class?”, with alterations in the survey to try and measure certain forms of response bias.

Senior Nico Riley looked to measure response bias with the question, “Are you fashionable?”

“I looked to see if a fashionable interview versus a more casually dressed interviewer would change the response” he said, “I asked 40 people in all, including the other interviewer, asking the first people we saw.”

“The results were pretty split. People seemed to have already known whether they were fashionable or not, they didn’t have their own perceptions. So the characteristics of the interviewer didn’t really affect them.

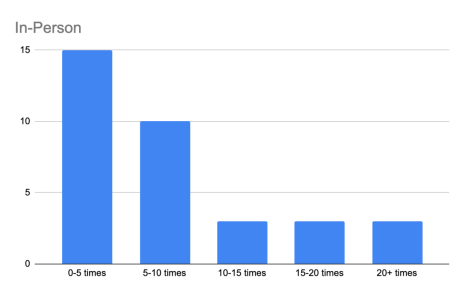

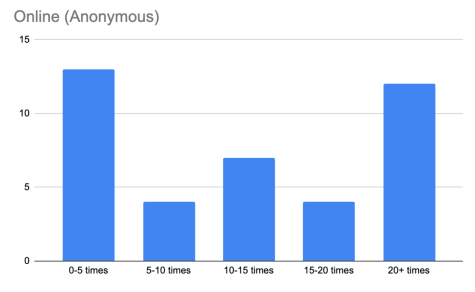

Senior Jocelyn Acevedo looked to see whether anonymous or in-person interviews would make a difference in responses to the question “How often do you lie?” with five options: 0-5, 5-10, 10-15, 15-20, and 20+ times a week.

“I would either walk up to people and ask them directly or hand them a piece of paper to answer anonymously. In total I asked 40 people in each group. People put that they lied more when it was anonymous than when it wasn’t anonymous.”

“I would either walk up to people and ask them directly or hand them a piece of paper to answer anonymously. In total I asked 40 people in each group. People put that they lied more when it was anonymous than when it wasn’t anonymous.”

The distribution of answers also changed in her survey, with more willingness to admit to higher ranges of lying than when asked in-person.

“People lied way more than I thought they would,” she said.