Great Gig in the Sky Presents Beck’s Odelay (Program)

May 1, 2015

STUDENT SHEPHERD: Gaela LaPasta

MUSICIANS:

Maya Bater, Hannah Weiss, Jansen Wenberg, Jonah Ury, Evan Vietorisz, Julius Rodriguez, Max Ishmael, Dante Moussapour, Al Daibes, Shoshana Chipman, Jared Foxhall, Trevor Dee, Harrison Guo, John Kinsley, I-Chen Cheng, Peter Nadel, Theodore Hoisington, Olivia Gibson, Runlan Yao, Suleng Tao, Anais Mazic, Abbey Frank, Noah Rosner, Ben Catania, Owen Lieber, Cian McGillicudy, Charles Woll, Spencer Berkowitz, Juliette Greene, Benjamin Zeitz-Moskin, Allegra Copland, Jasmine Esparza, Alison Maroukcoe, Haley Goodman, Julia Kane, Hannah Welles, Julia Murphy, Isa Alexander, Michelle Shear, Shirin Sabety, Gabby Bavaro, Maya Bater, Julia Kane, Daniel Cienava

Dohters

DJs:

Francesca LaPasta aka DJ C’P@$$

Juliette Greene aka DJ Qu3ntin

Kaspar Hudak aka DJ Zaspar

Assistant Technical Director: Ken West

Stage Manager: Robert Cott

Assistant Stage Manager: Jes Burke

Followspot Operators: Arran Fenniman, Zoe Palmer

TECHNICIANS:

Al Daibes, Jonah Dubin, Aka Ebling Okasaki, Juliette Greene, Ahnaf Taha, Henry Williams, Cesca LaPasta

VIDEO ARTISTS:

Phil Minton, Sam Coffey, Evan Lewis, Alex Kuznetsov, Annie Canning, Gaela LaPasta, Clara Meere-Weigel, Anais Mazic,

DANCERS:

Grace Brewster, Marleyna George, Jasmine Esparza, Lazarena Lazarova, Amalia Mayorga, Wendy Zhang, Meaghan Cunniffe, Al Daibes, Gaela LaPasta, Kintashe Mainsah, Julia Moore, Nicole Fitzgerald, Clara Meere-Weigel, WenXuan Ni, Hazel Kalderon, Cesca LaPasta

Special, huge thanks to our Artistic Shepherds, Jeff Carnevale, Vincenzo Galgano, Gilles Pugatch, and Janie Wallace!!!!!! You not only make this performance and experience possible, but you make it unbelievably joyous and oh so collaborative! #synergy

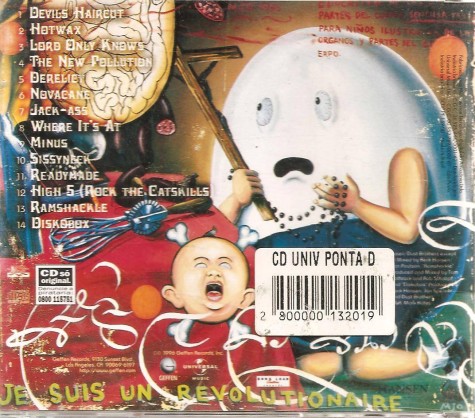

Odelay! Dramaturgical Musings

Few musical experiences are more spirit-draining than stumbling across washed-out versions of old anthems. Each time I hear Jimi Hendrix’s “Purple Haze” softened into grocery-store muzak or The Who’s “Won’t Get Fooled Again” used to sell cars, I know some angel in rock and roll heaven is choking on his own vomit. It is safe to say, though, that no track from Beck’s innovative Odelay! will get bleached into banality or corralled into commerce. Harsh sounds and unexpected mixes run through Beck’s songs: briars that keep trespassers out of the garden. Those thorny features, though, can also make the record uncomfortable for new listeners. Is this hip-hop or rock? Or country, even? And what’s with all the noise?

Odelay! has gotten me thinking about innovation and noise this year. The album was released in 1996, a full decade after my musical tastes had settled into the grooves laid down in my youth. So when I first listened to Odelay!, the music seemed to be pushing me away. Ouch, I thought, this doesn’t make me want to dance or sing along. Who’d want to listen to this? That question brought with it an image: I was no longer running free with the kids in the streets; I had become the old man on the other side of the fence shaking his fist at the kids to get off his lawn and turn off that NOISE!

Is that what drives musical change, one generation’s desire to create something that pushes against the previous generation? My aunt and uncle—the ones closest to my age, the fun ones—once asked what my favorite band was. When I replied “Talking Heads,” my aunt suddenly seemed a lot older, saying she didn’t know why bands lately used such ugly names. This from a woman who’d grown up listening to the electric guitars and free-love lyrics that made her parents cringe. Come to think of it, her parents had come of age listening to Bing Crosby and Frank Sinatra, who irked their elders by not singing on the beat. And before that, in 1914, Igor Stravinsky drove an audience to riot by playing music that broke the rules of nineteenth century composition.

So a new sound can build a sense of group identity by setting listeners apart from others who don’t get it. Odelay! seems to take that exclusion/inclusion principle to a new level. By mixing the boundary-defining sounds of so many genres, Beck in effect multiplies the barriers keeping out the uninitiated. The distortion-heavy guitars in “Devil’s Haircut” hearken back to the defining sounds of rock and roll; the screaming vocal that ends the song brings the idea of distortion up to the time of thrash metal. On the next track, “Hotwax,” the ragged harmonica playing across the twangy guitar starts that song with a bluesy feel, then morphs to the rhythmic, looped hip-hop screeches that suit the tight rap rhymes of the later lyrics. Next, the slide guitar and laid-back vibe of “Lord Only Knows” piles country and jam-band onto the heap. How many listeners have such wide-ranging tastes?

On the other hand, Beck’s use of so many different traditions—startling as it can be at first—doesn’t lead to cacophony. After several listenings,Odelay! begins to sound more like a crowd of American musical idioms all talking loudly in the same diner. The accents differ, but they find unexpected common ground. The jangled brass that punctuates “Devil’s Haircut” suits the tone of self-alienation created by the pervasive amp distortion. And the accordion and low-frequency bass that slip into breaks in “Hotwax” are not native to blues nor hip-hop, but it turns out that their sound feels right at home.

Innovation, while it might be jarring at first for listeners, grows from artists’ desire to explore and discover. Sometimes that exploration involves incorporating sounds from other traditions, as with Stravinsky’s use of folk melodies in his symphonic pieces or rock’s use of the blues. And Beck’s use of just about everything. Sometimes musicians make innovative leaps when they probe the possibilities of new technology—not just what was intended, but also what initially seemed like liabilities. Pushed to their limits or positioned improperly, electric guitars would distort tones or produce feedback. But musicians from Chuck Berry to Jimi Hendrix added those sounds to the rock palette, using what might have seemed like undesirable noise to convey youthful exuberance and altered consciousness. Hip-hop artists used a liability in LP technology to their advantage: vinyl albums made a scratching sound when bumped, but DJs turned what had initially been the sound of clumsiness into an agile feature of percussion. They also found other percussion opportunities in non-melodic bits—what could be called noise. Although musicians like John Cage and later the Beatles had been incorporating samples since mid-century, bands like Public Enemy and NWA found that by cutting the sample length down and looping it, they could make percussive effects from what had been melodic in the original (in other words, what mattered for DJs was the rhythm and stand-alone sound created by the sample, rather than the relation of its pitch to other pitches). Even the stutter-skip of CDs found its way into music–and onto prime time television as the speech pattern of Max Headroom. To tweak Marshall McLuhan’s proverb, the medium becomes the music. The unexpected sounds that accompany electric amplification or LP bits grow into key features in the sound of rock or hip-hop.

But why noise? Why have innovators been drawn to discordant and jarring sounds? Stravinsky had his devilish tritones. Beck has his slamming sound in “Computer Rock,” like an iron arm hitting a man repeatedly in the chest. Discordance in music seems especially characteristic of the twentieth century. Perhaps life has felt increasingly vulnerable to shock and dislocation. Industrialization and urbanization, genocide and terrorism, pollution and consumerism, racism and conspiracy theories, propaganda and social media: the fast-paced changes of the twentieth century and the scale of events—so much huger than any person can comprehend—make stability and unity feel out of reach. Melody and harmony slip into the realm of the ideal; dissonance and pounding sound more familiar.

Art is usually said to have two purposes: to entertain and to teach. I would add a third: to embody. In this third role music uses noisy elements to reflect the disordered experiences of its listeners. Janis Joplin’s straining voice in “Piece of My Heart” embodies the strain of desperate love; NWA’s jagged riffs and rhymes in “Fuck tha Police” embody the jagged resentment that grows from a life on the wrong end of a nightstick. Neither song fixes the problem, but putting those out-of-control feelings into a musical structure, the songs suggest some degree of order. In voicing our experience we take some control of it rather than letting it control us.

What’s more, this deliberate arrangement of what feels disordered has further effects over time. Our hunger for new sounds that express something of our experience develops into a taste for what others might call mere noise. Because the human mind is built to change, because we adapt—on all levels, from neurons to nations—we come to take aesthetic pleasure in those noises. We hear beauty when disruptive truths are played artfully.

Our impulse to find beauty in a second or eighth listening to a boundary-crossing record is, perhaps, the righteous flipside of our tendency to feel numb when we hear familiar songs played over and over in elevators. Beck’s Odelay! is a fitting album for the end of the twentieth century. It grapples with the fragmented and frenetic life that emerges out of mass-media irony (“Titanic, fare thee well”) and post-industrial consumerism (“Okay, now do you like designer jeans?”). It is cheeky and iconoclastic, confrontational and evasive. But underlying it all is a search for sonic connections, for unforeseen resonances. Beck weaves together the musical branches and roots that have splintered in so many directions. Odelay! reminds us that music comes not from the sounds we are given but from what we make of those sounds.

Paul West #theenchantingwizardofdramaturgy

If you are interested in reading about specific tracks on the album, you can find plenty of information online. Beck attracts fans interested in details of his production. Here are a two sites to start with.

http://whiskeyclone.net/disco/releaseinfo.php?discoID=11

to get lyrics, background, and very extensive notes on each track, click on a song title, then on the next page click on “version of” near the top

http://www.musictech.net/2014/11/landmark-productions-beck-odelay/

general overview and a paragraph on each track