Coronavirus and the European Union

April 24, 2020

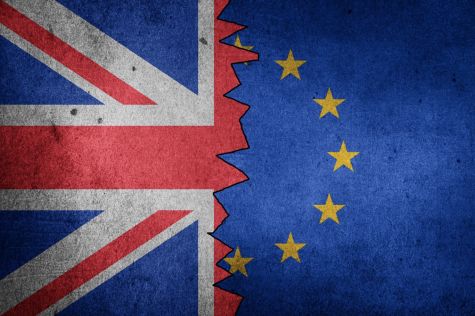

The borders in Europe are closed. The staggering accomplishment of free movement of people was reversed so quickly and unilaterally that it makes one question just how much unity there actually is in the European Union. So, what similarities are there between European countries during this coronavirus crisis? And what is breaking Europe apart?

One development that can be observed in many European countries at the moment is the rally ‘round the flag effect. The rally ‘round the flag effect describes the support of the government and governing politicians going up during a crisis. A drastic example for that can be found in Germany. The country’s chancellor boasts an approval of 64% according to a recent poll conducted by infratest dimap. This is her highest approval rating in her current term of office. The most stunning approval is that of Markus Soeder, the governor of the German state of Bavaria. The approval rating for his handling of the pandemic in his state is at 94% according to another infratest dimap survey. A similar trend can be observed in various other European countries, such as Austria, where chancellor Kurz’s approval rating has gone up to 76% by a recent Unique research poll, and Lithuania, where prime minister Skrevelnis’ approval rating has surged to 60% according to Baltijos tyrimai poll.

In Hungary, a novel “coronavirus bill” vastly extended the emergency powers of the current prime minister, Viktor Orban. The new law allows Orban to rule by decree for an indefinite period of time, essentially granting him unchecked and thus autocratic powers. In addition to the sweeping authority of the prime minister, the bill also states that those hindering the curb of the spread of the virus can be sentenced to up to five years in prison. Orban’s party – Fidesz – holds an effective two thirds majority in the Hungarian parliament. This means that the party can easily pass legislation, such as the “coronavirus bill,” even if there are strong concerns by the opposition parties. The move has been widely critiqued by rights groups and the Council of Europe, an international organisation with the goal of ensuring the respect and implementation of human rights. The latest developments regarding Orban’s emergency powers have triggered a strong support for removing the Fidesz party from the EPP, the largest political group of the European parliament. However, this attempt has not been successful, as the German member party of the EPP – the CDU/CSU – have opposed the measure.

On the economic side, the treasury secretaries of the various EU member countries have agreed to a 500 billion Euro bailout. The European Stability Mechanism, or ESM, will provide 240 billion Euro in additional credit lines. This money can only be borrowed for the “financing of the direct and indirect costs of health care, healing and prevention.” In addition to that, the European Investment Bank will supply companies with credit worth 200 billion Euro, mainly directed at small and mid-size enterprises. Lastly, a program called “Sure” will provide 100 billion Euro of additional help distributed by the European Commission.

Although a compromise was reached for the aforementioned bailout, there have been large divergences of opinion on another economic instrument, so called “corona bonds.”. These bonds are a form of joint debt issued by the governments of the Euro zone with the goal of financially stabilizing the Euro zone through the amelioration of the borrowing conditions for many countries within the EU. Various nations, such as Spain, Italy and France – the countries hit hardest by the coronavirus – have come out in favour of corona bonds, citing better conditions for an economic recovery and European solidarity as two arguments. The so called “frugal four,” consisting of Austria, Finland, Germany and the Netherlands, oppose the measure of corona bonds. Their main concern is the spreading of the risk of the bonds. If poorer countries failed to repay the debt, richer and more economically stable countries would have to shoulder the burden.

While EU countries have experienced some similar political trends and have managed to negotiate a European bailout, questions about European values and solidarity have emerged from Hungary’s move towards authoritarianism and the conflict around corona bonds. In a recent poll in Italy, conducted by Tecne, the hypothetical scenario of an Italian referendum on the European Union was presented. 51% of respondents would vote for remain, while 49% would choose to leave (14% of ‘don’t knows’ are excluded). This constitutes a 20 percent drop in the support of the remain side. It is a drastic development and reveals the disillusionment with the European response to the Covid-19 pandemic. Angela Merkel recently pointed out that the coronavirus crisis was the EU’s “biggest test since its founding.” The EU stands at a historic crossroads. It is a moment, in which decisive and cohesive action is more important than ever.