Children of the pandemic: exploring the challenges and coping strategies of the world’s youngest learners

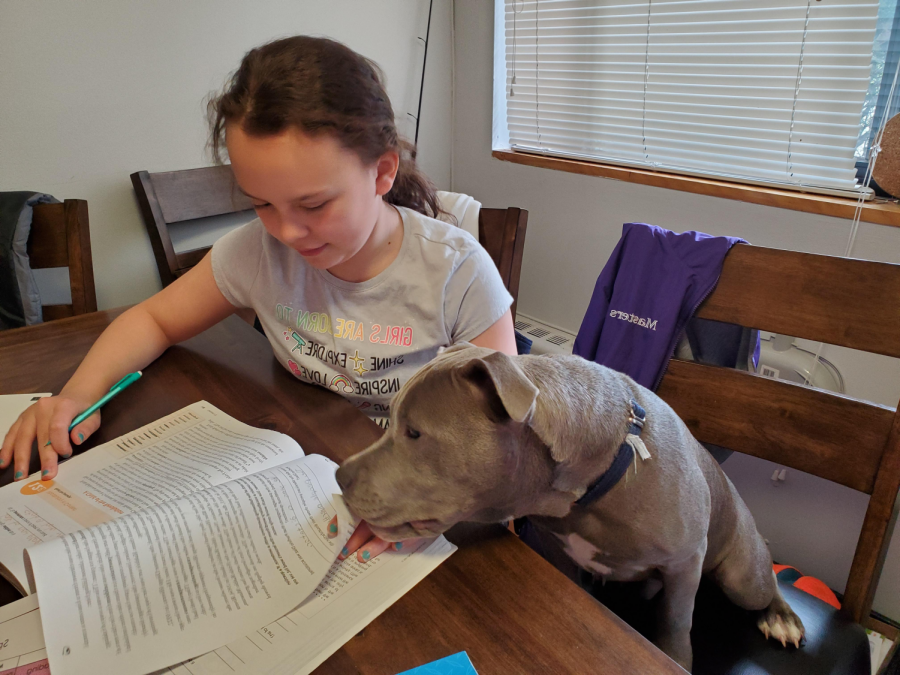

11-year old Abigail (Abby) Kaye, the daughter of eleventh grade Class Dean Shelly Kaye, studies at home accompanied by her family’s dog. Because both of Abby’s parents are teaching in person this fall, she’s had to take on more responsibility making sure she and her brother Gavin are present for their online classes. Kaye said, “It’s been difficult for me to accept that I’m turning it over to an 11-year old to manage her own schedule. Under normal circumstances, I would never expect anything like that.”

November 20, 2020

The initial thrill of learning from home that many young children experienced back in March has quickly faded into an endless stretch of fear, isolation and uncertainty. The pandemic is not only proving costly for their academic, social and emotional development, but has taxed parents and teachers, who have morphed from homeschool assistants, to scientists fielding questions about the virus, and psychologists attempting to calm their children in an age where peace of mind is seemingly nowhere to be found.

Tower Broadcast News Producer Logan Schiciano explores the challenges and coping strategies of the world’s youngest learners, their parents and teachers in a five-part special report. Click the “read more” button above to view.

Here’s an excerpt from each section.

Remote roadblocks

Head of Middle School Tasha Elsbach said her kindergartener would complain about not getting called on, her frustration reaching a point where she told her mother she was not going to speak anymore in class. “I’m going to mute myself!” – a proclamation that was ultimately short-lived. While Elsbach intervened in this instance to set things straight, she recalled other occasions where she simply could.

“I was her only playmate,” Elsbach said. “But a lot of the time I would be right there totally ignoring her, because I was working. One day she said to me, ‘I’m firing you. You can’t be my mom anymore. You didn’t spend any time playing with me.’ And I just felt like a horrible mom.”

A silver lining?

Being at home has allowed many families to share milestone moments together. English teacher Darren Wood said his two eldest children Mia and Luka were right there when their little brother Owen took his first steps.

Math teacher Marianne van Brummelen, the mother of three boys, said she witnessed the development of her kindergartener Cole’s reading skills first-hand. She explained that her children all love school but worried that if her middle son’s reading level didn’t progress, he would become frustrated.

“I didn’t want that to be the reason he didn’t like school anymore,” she said. “I was in such foreign territory trying to teach him this skill that is pretty complicated, but on the other hand it was really cool to be a part of that process.”

The talk about COVID-19

On a recent November night, at the Wood family dinner table, news broke that 28 year-old Mo Salah, a Egyptian professional soccer player, one of the family’s favorite, had tested positive for COVID-19. Wood recalled his children’s response: “Is he going to survive?” While the Wood parents have thoroughly explained to their children that young, healthy individuals, like Salah, are at extremely low risk of dying from COVID-19, Wood believes the question is indicative of the fear children are living with during this pandemic.

He said, “There’s underlying anxiety that they experience on a daily basis that’s not often visible to us. Even the reminder to put their mask on before they go outside signals to them that there’s something out there that they should be afraid of.”

The teaching transition

Hackley School Kindergarten teacher Kristen Adams said one of the hardest aspects for her has been resisting the urge to gravitate towards the children in times of despair.

“When they’re sad and crying, it’s hard not to go up to them and give them a hug,” she said. “Even from a work aspect, I can’t get down next to them and help them hold a crayon or scissors. Being hands-off is definitely tricky.”

Despite these restrictions, Hackley Lower School Psychologist Amanda LeTard has noticed a significant improvement in the children’s demeanor since the start of the school year.

“They’re just so happy to be back, to see one another, even if they have to sanitize everything they use and walk through the halls with ‘airplane arms’ to social distance,” she said.

Looking long term

LeTard said that remote instruction has eliminated children’s ability to utilize all five senses during the learning process, including development of fine motor skills like holding a pencil.

Dr. Julia Yang, a pediatrician at Northwell Health in Sommers, NY added, “We might be producing a generation of undereducated and screen-addicted children. The kids at every grade level are behind in all the basic skills and educators can’t decrease the benchmarks. We’re going to have to figure out a way to catch all the kids up, otherwise we’re going to have a real problem.”