Navigating the Use of Anonymous Sources in Journalism: Insights from Katie Way

February 25, 2022

The use of anonymous sources has always been a controversial topic. Some news outlets insist that unidentified sources are the only way to obtain certain information, while others don’t allow anonymous sources at all.

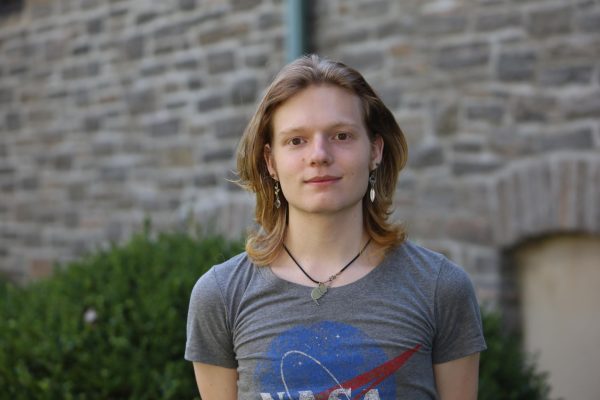

Katie Way, a staff writer at VICE Media, recently wrote an article on February 17th of 2022 titled, “How to Work With Incarcerated Sources as a Journalist,” which discusses the acquisition of information from incarcerated sources, as well as the protocols, process, and approaches for journalists to work with them. Katie Way graduated from Northwestern University in 2017 with a bachelor’s in journalism and a minor in creative writing. Based in Brooklyn, Way focuses on internet culture, work-life, policing, prisons, activism, and media.

Way expressed her experience working with incarcerated sources, stating, “Working with incarcerated sources is something I did for the first time in 2017 when I was writing for a website called Babe.” Way wrote about what life in prison is actually like, from the perspective of a 24-year-old girl who’d been in prison since she was 16. “We ended up getting in contact with her through a prisoner-penpal site.”

Way further elaborated on her experience working with complex sources, especially anonymous ones, “On the anonymous source front, it depends on what story you’re working on—so how sensitive is the information, and what is the publication you’re working with policy on anonymity.” Under AP rules, to use anonymous material, it has to be fact–not speculation or opinion, vital to the report, and only available under the conditions of anonymity imposed by the source. The source must also be considered reliable and have the capacity to have direct knowledge of the information. However, each news outlet has a different policy on how and when to use anonymous sources. Way says, “There are some publications that just won’t do [anonymous sources], and some will do it at the drop of a hat.”

In Way’s opinion, when and how to use anonymous sources is relatively circumstantial. “I don’t have a strict hard-and-fast no or yes, but a source is more likely to offer it than I am to ask for it.” Without a rigid philosophy, Way leans into her instinct on whether it’s worth it to use an anonymous source, or if instead, there is a better alternative. Way says, “That stuff tends to feel kind of intuitive. If an anonymous source reaches out to you, and they’re being aggressive or they’re being shady or something, then honestly, if what they’re saying is true but they’re being sort of withholding from you, there’s a scenario where you can try to find other sources who will go on the record or other people who will show you the documents you need.” This seems to reflect others’ beliefs on using anonymous sources–that unless the information can only be obtained using that particular source, it’s likely not worthwhile. This also echoes Tower’s unwritten approach, that trying to find a source that is instead willing to go on the record, rather than an anonymous one, is consistently more fitting.

The most prominent concern around using anonymous sources is their reliability. It’s difficult for readers to evaluate the reliability and objectivity of a source that’s unidentifiable. The story’s trustworthiness decreases when it depends upon details from anonymous sources, which can lead to doubt of the news outlet that published the piece. Unknown sources may decide to remain unidentified because they’re not confident the information they’re sharing is sure to be the truth, or perhaps they’re even completely aware that what they’re saying is untrue. Way believes it’s the journalist’s responsibility and obligation to ensure the information they’re putting out to the public is accurate, especially when working with anonymous sources. “[Verifying sources] is definitely something that has to happen during the reporting process, before you even take the time to start writing the story.” Way continues, “I guess it depends on the situation, but you absolutely–as early as possible–need to say, ‘I need to know that you are who you say you are, I need you to forward me emails, I need to see documents.’” Most media outlets’ guidelines on anonymous sources require the authors and editors of a piece to know who the source is, even if they’re unknown to the public. This ensures that the writers can effectively assess the source’s dependability and impartiality. “You, as the reporter and your editors, know this person’s identity–you know they’re telling the truth because you’ve gotten documentation from them.” Way emphasizes the importance of confirming your claims, stating, “The last thing you want to do is pour time and energy into reporting a story and then–heaven forbid–it comes out, and you find out it’s not true.”

Even in difficult situations, substantiating a source always takes precedence. Way says, “It can be hard because sometimes people come to you with really sensitive stuff, and you don’t want to push, but you really do need all the information, and if it’s too hard for someone to share that with a journalist, then they shouldn’t be participating in journalism.”

Due to the perceived unreliability of anonymous sources, Way wants to emphasize that most of the time, unknown sources have at least some kind of backing. “I’m glad to see a young person like you learning about journalism in high school because I feel like a lot of school didn’t do that kind of education, so a lot of people see an anonymous source and think, ‘Oh, it’s just a random person!’” Despite this concern around anonymous sources, 82% of U.S. adults say that there are times when it is acceptable for journalists to use unidentified sources (PEW Research Center 2020).

When using anonymous sources, various organizations have provided guiding principles to help journalists navigate this ground, with most of the principles being very similar or identical to each other. The most prominent of these include:

- Only use anonymous sources if there is no other way to get the information. (AP, JEA, SPJ)

- If the source isn’t reliable, don’t use them. If you don’t know if they are reliable, the answer is likely to be they aren’t. (AP, JEA, SPJ)

- While the public shouldn’t know who the source is, you should be aware of who they are. (AP, JEA, SPJ)

- If you promise confidentiality, you must keep the source’s identity confidential. (AP, JEA, SPJ)

Using the information you’ve learned throughout this article, work through these scenarios:

- A teacher had recently been dismissed from your school for problematic comments to students, and you decided to write a piece regarding it. You find students from the teacher’s classes and ask them about their experience with any concerning comments the teacher had made. Everybody except one student is willing to talk to you. The one student tells you about their individual dislike for the teacher and why the student personally believes they weren’t a good teacher. The student permits you to use their quotes in your story under the conditions that you will not publish their name. What do you do? Why?

- You’re a journalist working for a major news outlet, and a source reaches out to you and wants to whistle-blow. He is an employee of the CIA and holds “sensitive documents” that he wishes to share. These documents show various clear human rights violations that the United States has committed in the last decade and are incredibly shocking to you and your editors. How do you approach this?