Fact or fiction? In media, the line is blurred

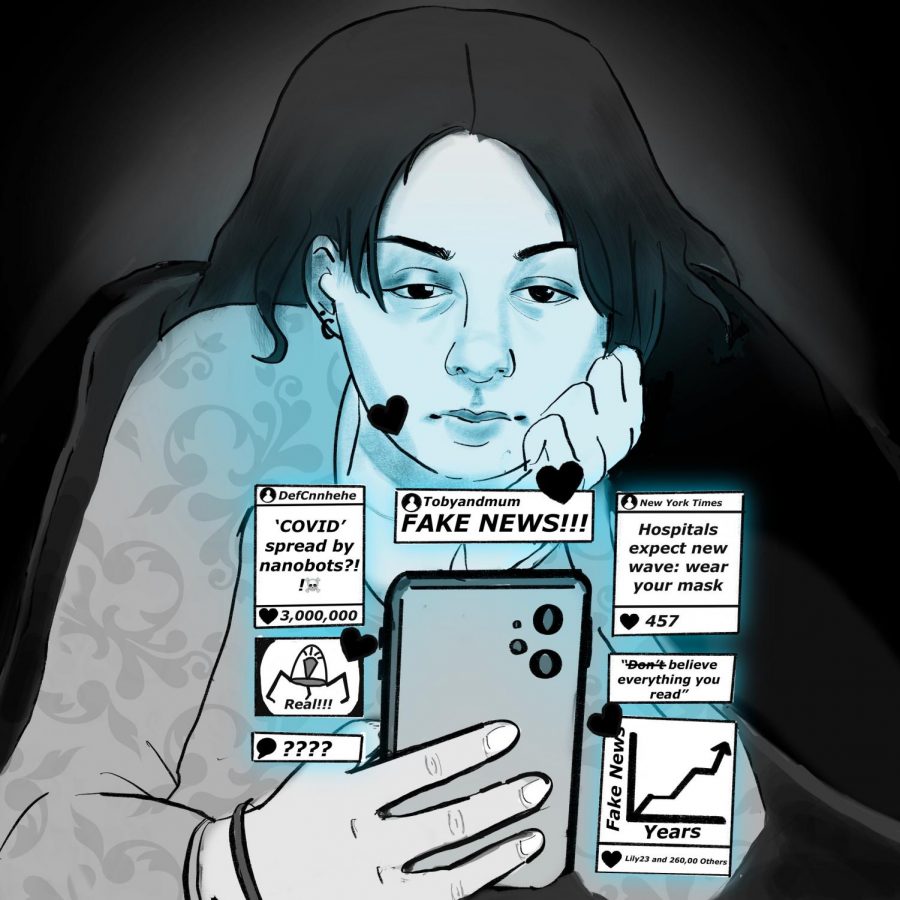

While scrolling through social media, a teenager is grappling understanding what information to believe in a world of media bias. (Phoebe Radke/Illustrator)

October 27, 2021

We are experiencing a new virus. But unlike Covid, there is no vaccine to stop the spread. It is contagious. It is manipulative. Media Bias has overtaken the planet.

Media bias occurs when publication reliability is skewed, and when opinions get in the way of how and what is being covered.

There has been a rapid rise in media bias over the past five years due to the recent political climate – specifically a division between the American people. However, this is not new: as long as American politics have been around, so has the famous saying, “fake news”.

It started in 1807 when Thomas Jefferson talked about recent coverage in American newspapers.

He said, “Nothing can now be believed which is seen in a newspaper.”

200 years later, “fake news” has become the phrase of the era. In an attempt to defend his administration from critical coverage, Donald Trump noted the “tremendous disservice” of the public press to the American people.

He said, “I’ve never seen more dishonest media than, frankly, the political media.”

Colleen Roche, a political science and history teacher at Masters, noted that it was during the 2016 presidential election when misinformation through social media hit a dangerous peak, referring to the Russian creation of fraudulent social media accounts used to influence American voters.

Roche said, “I think that’s when we first became aware of the ability of these platforms to be so grossly manipulated.”

52% of American people receive “news or news headlines” from Facebook. Among teenagers, 50% use Youtube as a primary news source. Of these 50%, 60% say they receive their information from celebrities and influencers as opposed to news networks on the platform.

Following the 2016 presidential election, Stanford History Education Group released a report noting students’ inability to determine the credibility of information found on the internet. Sam Wineburg, founder of SHEG, said, “Many people assume that because young people are fluent in social media they are equally perceptive about what they find there…our work shows the opposite to be true.”

Stanford’s Graduate School of Education conducted a study where they shared two different posts declaring Donald Trump’s candidacy for president to a group of high school students. The purpose of this experiment was to evaluate their news literacy and judgement when using platforms like Twitter and Facebook. One post was from Fox News, while the other came from an account that “looked like Fox News.” While 25% of students recognized the difference in the blue checkmark, 30% actually found the second account to be more ‘reliable’ given their usage of “key graphic elements”.

Senior Kwynne Schlossman, social media manager of Tower for the 2020-2021 school year, reflected upon her experience posting to a younger targeted audience.

She said, “Social media can be very misleading. After having the opportunity to work in the field for a little, I got to see how much research you must do to make sure the information you are sharing is correct and accurate.”

Elijah Emery ‘19 worked as a social media manager during the campaign of Andom Ghebreghiorgis, a left-leaning candidate for New York’s 16th congressional district election in 2020. Emeory talked about how from a political lens, when looking for detailed information, social media isn’t the most effective source of information.

However, if one is looking for a popular opinion, it can be a very productive resource, and it’s up to the audience to decide which information to digest and which to scroll past.

Emery said, “There’s tons of information out there and much of it put out by the vast majority of credible people is not going to be inaccurate. The question: are they more accurate than a competing narrative?”

But, it’s not just teenagers. Due to the rapid posting, resharing, and spreading of information in the media, any social media user may have a challenging time discerning reliable information posted online. As mentioned in a MIT 2018 study on social media incredibility, “Falsehoods on social media are 70% more likely to be retweeted than the truth.”

Despite the evidence supportingmedia illiteracy among the American people, Roche noted how the vast majority of Americans still lack the ability to distinguish reliable to unreliable information shows that we have a lot more work to do.

She said, “[On a nationwide level,] we might ask what the individual person is doing about it? Not a lot.”